In the time it takes you to read this article, you’re likely to breathe a few dozen times. Some animals don’t breathe as often, and they don’t require nearly as much oxygen. The Loggerhead sea turtle, for example, can take one breath and stay underwater for about 10 hours. Still, it’s long been thought that all animals need to breathe oxygen to stay alive.

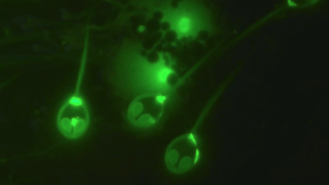

But then scientists discovered Henneguya salminicola, an 8-millimeter parasite that doesn’t need oxygen to live, and cannot process it as other animals do. The findings are published in a paper in the journal PNAS.

All other animals have mitochondria, which are organelles that act as the “powerhouse” of the cell by breaking down nutrients and converting them into energy. One way mitochondria do this is by converting oxygen into a fuel called adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which drives processes like muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, and chemical synthesis. This conversion process is called aerobic respiration.

But H. salminicola — a cnidarian animal related to jellyfish and coral — don’t have mitochondria, and therefore can’t perform aerobic respiration. Lead study author Dorothée Huchon discovered this as she was sequencing mitochondria across Myxozoa (a class of parasites).

“My goal was to assemble mitochondrial genome to study its evolution in Myxozoa and… Oops, I found one without a genome,” she told Vice. “I first thought that the lack of mitochondrial genome among the DNA sequence was the result of a bug in genome analyses. But then I realized that it has lost not just the mitochondrial genome but the whole set of protein genes that interact with the mitochondrial genome and all the majority of genes involved in respiration.”

An evolutionary advantage

Losing that mitochondrial genome appears to have been a less-is-more type of advantage for the parasite.

“Myxozoans have gone through outstanding morphological and genomic simplifications during their adaptation to parasitism from a free-living cnidarian ancestor,” the authors wrote. “As a highly diverse group with >2,400 species, which inhabit marine, freshwater, and even terrestrial environments, evolutionary loss and simplification has clearly been a successful strategy for Myxozoa, which shows that less is more.”

The researchers aren’t quite sure how H.salminicola breaks down nutrients without oxygen. One possibility is that it absorbs molecules from its host. It’s hard to tell, however, because the researchers analyzed dead parasites — they’d need to look at parasites living within the fish to get a better understanding of how the creatures operate.

The discovery highlights how much scientists still have to learn about the diversity of life on Earth. Atkinson told CNN that he expects H.salminicola isn’t the only animal that can survive without oxygen, or in even “weirder modes of existence.”

The search for alien life

One interesting implication of the discovery is what it means for the search for alien life. It’s long been thought that, if aliens exist, they’d likely breathe oxygen. After all, it’s the best element that we know of for producing large amounts of energy for metabolism, allowing us to “grow large, run and jump and think,” as David Catling, a planetary scientist at the University of Washington, told Forbes.

“Because of oxygen’s chemical advantages and the history of complex life on earth is so intertwined with oxygen levels,” he said. “I think E.T. would also breathe oxygen.”

This is one reason why many think Earth-like exoplanets with atmospheres that likely contain oxygen would be good candidates for harboring alien life. But, in a small way, the newly discovered parasite gives reason to think that the search for alien life — and their life-supporting planets — might be far more complicated.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.