From health concerns to funding, there’s no shortage of obstacles preventing humans from traveling beyond our solar system. But the main obstacle is propulsion: Our spacecraft are simply too slow and too reliant on fuel to realistically make a voyage to Alpha Centauri, the closest star to our Sun.

So, what do we need? Something like a reactionless drive — an engine that moves a spacecraft without exhausting a finite stock of propellant. So far, such a device only exists in science fiction. But for the past few decades, physicist Jim Woodward has been trying to change that.

The 79-year-old physics professor has developed a thruster design that he hopes will serve as a proof of concept for how humans can someday achieve interstellar travel. Called the Mach-effect gravitational assist (MEGA) drive, the device only requires a source of electricity to achieve thrust.

Early tests have shown mixed results. Woodward himself was only able to demonstrate miniscule amounts of thrust, while other teams reported little to no thrust when trying to replicate his experiments. Still, the design intrigued NASA enough to award Woodward $625,000 in funding between 2017 and 2018.

What’s more, in 2019 Woodward and his collaborator and fellow physicist Hal Fearn reported a major breakthrough after redesigning the thruster’s mount — a tweak that produced “more than 100 micronewtons, orders of magnitude larger than anything Woodward had ever built before,” as a recent feature in Wired notes.

(To be sure, the level of thrust we’re talking about is barely enough to visibly move an object across a table. But if the results are confirmed, it would suggest the technology could be scaled up.)

Woodward’s system is based on ideas that 19th-century physicist Ernst Mach proposed about inertia, which is an object’s tendency to stay at rest unless acted upon.

In simple terms, Mach’s principle argues that distant matter causes local inertial effects. So, a star in a far away galaxy has some effect on the inertia you encounter when you push a shopping cart. That’s the idea, anyway. (Woodward gives a comprehensive breakdown of his views on Mach’s principle in this blog post.)

In the 20th century, Albert Einstein incorporated Mach’s ideas into his theory of general relativity, essentially arguing that gravity and inertia are fundamentally linked. But the broader physics community later rejected this view of inertia, largely because of a 1961 paper that showed inertia to be unrelated to the gravitational influence of distant matter.

Still, Woodward believes Einstein had it right all along, and that, under this framework of inertia, it’s possible to develop propulsion systems that require only an electrical charge, not fuel. The key element of his thruster is a stack of piezoelectric crystals, which produces an alternating electric field when voltage is applied to it, as Woodward explained:

“Piezoelectric crystals are electromechanical devices, which means that when you apply the voltage, they mechanically expand & contract depending upon the sign of the voltage. So by applying a voltage, you’re causing an E/c² energy fluctuation in the stack no matter what they do mechanically, and you’re also producing an acceleration because of the changing dimensions of the stack due due to electromechanical effects, which also causes the acceleration required couple the device to the large gravitational field.”

“The trick is timing the energy fluctuations and mechanical oscillations correctly, which requires using two frequencies — at the first and second harmonics, and it’s the second harmonic that actually produces thrust.”

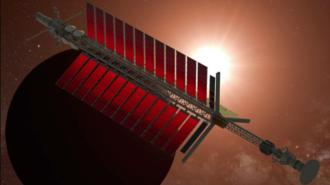

Woodward and his colleagues have even drawn up plans for a spacecraft that would utilize the MEGA drive. Called the SSI Lambda, the craft would feature piezoelectric crystals and a small nuclear reactor to produce electricity.

“The SSI Lambda probe using MEGA drive thrusters is a truly propellantless-propulsion spacecraft,” the team wrote of the design in its report to NASA. “It can travel at speeds up to the speed of light in a vacuum with only consumption of electric power. No other method for travelling to the stars and braking into the target system has been put forward to date, which also has credible physics to back it up.”

After the COVID-19 pandemic settles down, other scientists and engineers hope to put Woodward’s designs to the test. The results of those experiments should reveal whether he’s onto something. To some experts in the field, the odds are slim. But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth investigating.

“I’d say there’s between a 1-in-10 and 1-in-10,000,000 chance that it’s real, and probably toward the higher end of that spectrum,” Mike McDonald, an aerospace engineer at the Naval Research Laboratory in Maryland, told Wired. “But imagine that one chance; that would be amazing. That’s why we do high-risk, high-reward work. That’s why we do science.”

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.