After Hurricane Florence, reports started rolling in of “giant mosquito” sightings – and bitings – throughout North Carolina. What’s going on with these mega mosquitoes that can be as big as a quarter?

As a mosquito biologist, I often get asked to identify a mosquito based upon someone’s verbal report of the little buggers. I usually do OK with an educated guess based on descriptions like “It had striped legs, and was brown” or “It looked kind of purple.”

What I have always struggled with is when someone says “It was little” or “It was pretty big.” For the most part, size is not a good identifying feature of the common mosquitoes Americans encounter close to home.

This is because you can grow relatively large mosquitoes or small ones just depending on the conditions where they grow up – what entomologists call their larval environment. If the larval environment has few other competing mosquitoes, or is rich in nutrients, or has a cool temperature, the result is larger adult mosquitoes.

There are a couple of species of mosquitoes that are truly gigantic, though. If someone says they saw a big mosquito, and I follow up with “big for a mosquito, or too big to even be a mosquito?” and they say “too big to be a mosquito, but it was biting me,” then I know we truly have one of a couple species of “giant” mosquitoes.

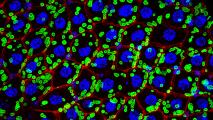

Under normal circumstances, these giant, biting mosquitoes – known locally here in North Carolina as “gallinippers” or scientifically as Psorophora ciliata or Psorophora howardi – are quite rare. They are two of about 175 species of mosquitoes we have in the United States. Their moment in the spotlight comes after major flooding events, like we had with Hurricane Florence. These mosquitoes can be as much as three times larger than their more typical cousins.

The gallinippers belong to a genus of mosquitoes that specialize in responding to floods. Females produce lots of eggs, which they spread out around areas that might flood, such as wet meadows, floodplain forests or even agricultural land. Those eggs are resistant to desiccation – that is, they aren’t damaged by dry conditions – so they can wait around for a flood the following year, forming an “egg bank.”

The eggs are fertilized as the female lays them, from sperm she’s stored during mating. In order to get the blood meals necessary to make many eggs, these mosquitoes are aggressive feeders on mammals, and maybe other vertebrates occasionally.

But evolving to a giant size doesn’t seem necessary to carry out these tasks. Indeed, many other species in this genus are not giants; they’re more typically mosquito-sized. So what separates the gallinipper?

One possibility is the fact that gallinippers, as larvae, prey on other mosquito larvae. Perhaps their size is an adaptation to consuming other floodwater mosquitoes, allowing them to more easily capture and consume smaller species? The more typical-sized mosquitoes that use floodwaters are not predators. Size may also allow them to produce many more eggs, which can also be an advantage when the floodwaters come.

Gallinippers have a painful bite that is usually well noticed by human victims, so the large numbers that emerged after Florence have received lots of attention.

While being bitten by a giant mosquito may not seem like a great thing, there are reasons to take heart. First, these mosquitoes likely get just one good blood meal in their lives, limiting their ability to transmit a pathogen.

As far as entomologists know, they don’t transmit any pathogens to people. And since, as larvae, these giants eat other mosquitoes, maybe one big bite is worth 10 small ones? Finally, it’s a great post-hurricane brag to announce “I got bit by a giant freakin’ mosquito!”

Other good news is that the adults likely don’t live more than a couple of weeks, so the great boom of mosquitoes from Florence is winding down. Of course, now it looks like Hurricane Michael may bring about another round of gallinippers. Winter does end the most immediate threat, but all those eggs are still out there, awaiting next year’s floodwaters.

![]()

Michael Reiskind is an Assistant Professor of Entomology at North Carolina State University. This article was originally published at The Conversation.