In the 1980s, scientists discovered an enzyme that repairs and can protect your DNA from some of the ravages of age. Unfortunately, they didn’t know what it looked like, how it fit together, and therefore how to target it with drugs.

For over 20 years, UC-Berkeley researchers have been trying to scan one of these elusive enzymes. This year, they succeeded, and we finally have a detailed picture of an enzyme that could play a key role in fighting both aging and cancer.

Tearing Pages from Your Genome: Every time a cell divides, it has to copy all your DNA, stored in 23 strings called chromosomes.

If you’ve ever braided hair, you know there’s always a bit left over at the end, a little tuft sticking out past the hair tie. Copying DNA is like that. The chromosome can’t zip itself up all the way to the end, so it just trims off that last frayed bit—effectively tearing out a few “pages” of DNA every time.

To avoid losing anything important, chromosomes have a cap on each end called a telomere, which is a string of meaningless DNA—like blank pages that you can afford to rip out.

Your Biological Clock: Unfortunately, you’re stuck with the number of blank pages you got when you were born. Over time, your telomeres shrink, and there’s less and less protection for your real DNA, making damage more likely.

After a cell has divided 50 or 60 times, telomeres have been cut down to almost nothing, and it won’t divide at all anymore. That means your ability to make new cells (and therefore easily repair DNA, organs, and tissue) declines as cells get older.

Why Things Fall Apart: Many scientists speculate that depleted telomeres play a key role in explaining why aging makes our health and abilities all decline at the same time—things just seem to fall apart. (Turns out Yeats was wrong: the centromere is fine, it was the ends that cannot hold.)

That sounds gloomy, but it’s not all bad. Telomeres put cells on a clock, but they also put them on a leash: limiting cell growth can protect us from cancer, when cells just go crazy and multiply out of control.

Topping Off: In the 1980s, Berkeley scientists discovered an enzyme that extends telomeres (imaginatively called telomerase). It adds a few blank pages of DNA to your chromosomes, effectively extending the life of the cell.

But the enzyme is only expressed in embryos, where it builds up the telomeres you’ll use your whole life, and it’s rarer in adult cells. This made it hard to find in one piece and in large enough quantities to study. But after 20 years of searching, the Berkeley team managed to purify enough enzyme to scan it with an electron microscope.

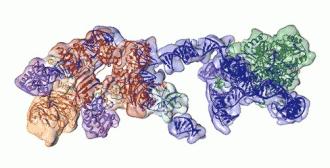

Rotating view of telomerase, showing RNA backbone in blue, associated proteins in orange and red, and the heart of the enzyme, a reverse transcriptase, in green.

Now that we understand how all the proteins in it work and fit together, we can start to figure out how to make drugs that target it.

The Last Wrinkle: When telomerase was first discovered, there was a lot of hype about a “cure for aging.” That turned out to be very premature, since we’ve only just now managed to get a good look at it.

But we’ve also come to appreciate the tradeoffs that evolution has been facing: short telomeres are not just dooming us to a declining old age—they also help stop cancerous cells from proliferating. That’s especially valuable for the elderly, who are more susceptible to cancer from a lifetime of mutations and DNA damage all over their chromosomes.

And, in fact, cancerous cells have been found to turn telomerase back on to speed their own growth. A drug that just indiscriminately took the brakes off cell division might reverse some effects of old age, but it could also unleash tumors. That’s why some researchers are also looking for ways to block or reverse engineer telomerase to fight cancer growth.

Either way, discovering the structure of this enzyme is a big breakthrough in the battle for longer, healthier lives.