What strategy do you use to make tough life decisions like whether to end a relationship, quit your job, or go back to school?

Maybe you weigh the pros and cons. Maybe you go with your gut. Or maybe, if you’re like most people, you simply do nothing. After all, we have a cognitive bias that tends to make us prefer the status quo, and focus more on the potential losses involved with change rather than the potential benefits.

But here’s a simpler strategy: When you’re indecisive about a big life decision, choose the path of change. That’s the takeaway of research recently published in the Review of Economics Studies by Steven Levitt, an economist at the University of Chicago and host of the “Freakonomics” podcast.

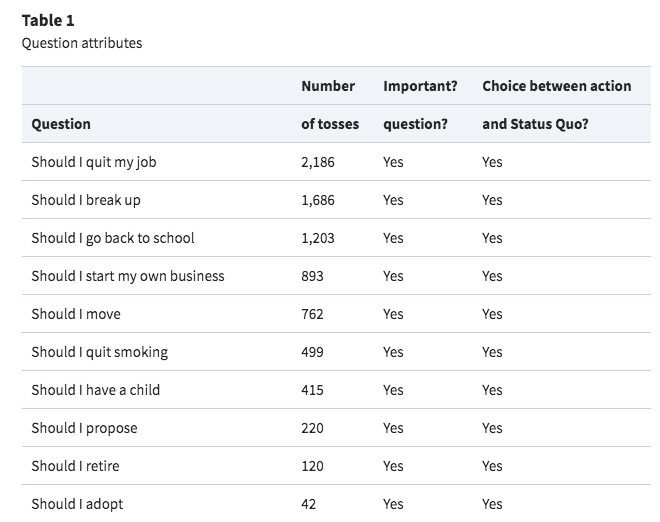

For the study, Levitt asked people who were facing tough decisions to flip a digital coin on the website FreakonomicsExperiments.com, created in 2013. The coin tosses were randomized, with one side representing change, the other status quo.

Some decisions people were stuck on: Should I quit smoking? Should I adopt? End my relationship? Get a tattoo? Rent or buy?

The study asked more than 20,000 participants to make whichever decision the coin toss directed, and then report back on how things played out after two and six months.

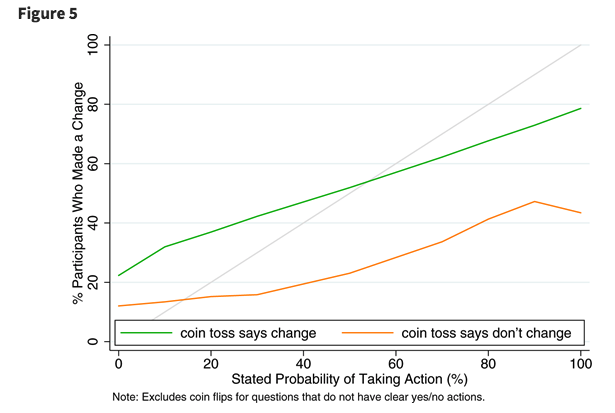

Of course, not everyone followed through. The two-month survey found that participants chose change less frequently than they had initially predicted they would. After six months, however, this bias toward inaction disappeared.

But most surprising were the results on well-being. At both the two and six-month marks, most people who chose change reported feeling happier, better off, and that they had made the correct decision and would make it again.

“The data from my experiment suggests we would all be better off if we did more quitting,” Levitt said in a press release. “A good rule of thumb in decision making is, whenever you cannot decide what you should do, choose the action that represents a change, rather than continuing the status quo.”

The study had some limitations. One is that its participants weren’t selected randomly. Rather, they opted in to the study after visiting FreakonomicsExperiments.com, which they likely heard about from the podcast or various social media channels associated with it.

Another limitation is that participants whose decision didn’t play out well might have been less likely to report back on their status after two and six months. So, the study might be over-representing positive outcomes.

Still, the study does suggest that people who are on the margin of a tough decision — that is, people who really can’t decide which option is best — are probably better off going with change.

“If the results are correct, then admonitions such as ‘winners never quit and quitters never win,’ while well-meaning, may actually be extremely poor advice,” Levitt writes.

Levitt isn’t suggesting you flip a coin to make all decisions. (After all, Donald Duck already experimented with this irrational decision-making strategy in the 1952 Disney comic “Flip Decision”, where he practices a pseudophilosophy called “flipism.” Spoiler: It didn’t go well.) But coin-flipping does seem to have some benefits. In the study, Levin notes that some people might prefer surrendering their fate to randomness in order to avoid regret.

“If regret is a product of decisions that one has control over,” Levin writes, “giving up control to a randomizing device may, lessen possible regret, thus enhancing expected utility.”

But you can also use randomness a bit more rationally. When facing a tough decision, you could flip a coin and, upon seeing the outcome, notice whether you feel relief or dread. If you feel relieved, that’s probably the path you should choose.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.