Researchers at Imperial College London’s Centre for Psychedelic research have tested a common antidepressant head-to-head against psilocybin for depression — and the magic ingredient in magic mushrooms performed at least as well as the traditional meds, and possibly even better.

The study, which is the first to test the psychedelic directly against a commercial antidepressant, has drawn strafing fire for its shortcomings — weaknesses that even the authors concede — and so the result is not definitive yet.

“One of the most important aspects of this work is that people can clearly see the promise of properly delivered psilocybin therapy by viewing it compared with a more familiar, established treatment in the same study,” Robin Carhart-Harris, head of the Centre and study designer and lead, said in a release.

“Psilocybin performed very favourably in this head-to-head.”

Psilocybin for depression: As regular Dope Science readers know, the field of psychedelic-assisted therapy has come back into vogue, garnering strong institutional support from august names like Johns Hopkins, NYU, and Mount Sinai.

The drugs under investigation have at times shown almost shocking, set-scientists’-Spidey-senses-tingling efficacy against some intractable mental health disorders.

MDMA and ketamine hold particular promise, with MDMA assisted therapy seeming especially effective for PTSD and ketamine being an unusually fast-acting antidepressant.

Using psilocybin for depression is one of the more robust areas of study, insofar as psychedelics go. But Carhart-Harris’s study is the first to compare the compound against one of our most commonly prescribed antidepressants.

Standard of Care: The ICL team’s paper, published in the NEJM, set up a showdown between psilocybin and its real world competitor — the current “standard of care” for treating depression.

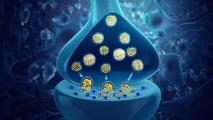

In the red corner was escitalopram, better known as Lexapro — the established treatment. This common antidepressant is from a class of drugs called selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

The phase 2 trial enrolled 59 patients with moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder, split into psilocybin and escitalopram arms.

The 30 people receiving psilocybin for depression treatment had an initial dose of the psychedelic, with a follow up three weeks later. In addition, so they wouldn’t know which arm of the study they were in, they were given a six-week course of placebos to pop, beginning with one a day and doubling to two a day after their second psilocybin dose.

On the escitalopram side, 29 patients had the same pill schedule as their counterparts, except in place of a placebo, they took the SSRI. But to make sure they didn’t know for sure which treatment they were getting, they also went to dosing sessions, where they received tiny doses of psilocybin — a dose too small to cause a trip.

No severe adverse events were reported.

The researchers used several measures of depression to determine patients’ conditions, and all but one measure showed psilocybin patients reporting greater improvements in their wellbeing, NBC News reports. The only measure of depression that didn’t favor psilocybin was a draw.

The psilocybin group also reported fewer instances of side effects, like dry mouth, anxiety, and sexual dysfunction.

“In our study, psilocybin worked faster than escitalopram and was well tolerated, with a very different adverse effects profile,” David Nutt, principal investigator of the study, said in the release.

Unfortunately, that one measure that didn’t favor psilocybin — a questionnaire known as QIDS-SR-16 — was chosen in advance as the primary measure of the study. (Researchers must decide this before the data comes in, so they can’t move the goalposts to fit their data.)

It showed no statistically significant difference in how well the treatment worked for each group; hence, the researchers can only say that psilocybin for depression treatment appeared to work as well as the SSRI.

The cold water: “Out of the nearly dozen clinical scales they used to measure depression symptoms, they somehow happened to pick the one scale that showed no difference between the two treatments as their major (primary) outcome measure,” Boris Heifets, a Stanford neuroscientist (unaffiliated with the study), told STAT.

While the study had “many strong positive signals” that psilocybin for depression works better than the SSRI, the study’s design prevented any strong conclusions from being drawn, Heifets said; so “it’s a wash.”

For their part, Carhart-Harris and company acknowledge the limitations of their study. Among them are the small sample size, and that the participants were mostly white, well-educated, and male.

The study is “not a quantum leap,” Guy Goodwin, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, told the BBC. “It is under-powered and does not prove that psilocybin is a better treatment than standard treatment with escitalopram for major depression.

“However, it offers tantalising clues that it may be.”

Pioneering psilocybin researcher Roland Griffiths — of Johns Hopkins — seemed a bit more bullish, telling NBC the study “is huge because it’s showing that psilocybin is at least as good — and probably better — than the gold standard treatment for depression.”

Carhart-Harris told STAT he regretted the choice of the questionnaire as the study’s main outcome measurement, but he noted that the measurement is widely accepted by regulatory bodies around the world, which makes it important for drug trial research.

Even still, when combined with other promising studies looking at psilocybin for depression, the work could be valuable — and as always, more research will be the key.

“We look forward to further trials,” Nutt said, “which if positive should lead to psilocybin becoming a licensed medicine.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.