A team led by researchers at Barcelona’s Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) have created what they call a “living medicine” to fight lung infections.

Their work, published in Nature Biotechnology, engineers one form of bacteria to fight another — the dreaded Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can be particularly tricky to treat. By sending a living organism to fight P. aeruginosa, in combination with antibiotics that would likely fail on their own, the team was able to “significantly” reduce lung infections in mice.

“We have developed a battering ram that lays siege to antibiotic-resistant bacteria,” María Lluch, co-corresponding author of the study and chief science officer at CRG spin-off company Pulmobiotics said.

“The treatment punches holes in their cell walls, providing crucial entry points for antibiotics to invade and clear infections at their source. We believe this is a promising new strategy to address the leading cause of mortality in hospitals.”

Researchers have engineered bacteria to become a “living medicine” to fight lung infections.

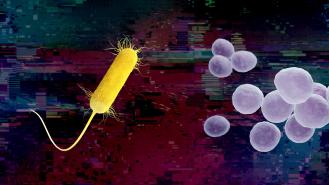

What is Pseudomonas aeruginosa? A rod-shaped bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa has a combination of traits which makes it an “extremely challenging organism to treat in modern-day medicine,” LSU’s Mina G. Wilson and Shivlal Pandey explain.

The bacteria’s natural antibiotic resistance, its “extreme versatility,” and its “wide range of dynamic defenses” — including anti-antibiotic enzymes and tiny pumps to remove medications that can kill it — make it difficult to treat.

P. aeruginosa infections are common in immunocompromised patients; people with implanted devices are at particular risk, thanks to one more nasty trick up its sleeve: the ability to create biofilms. In a biofilm, bacteria layer across one another and create a matrix, a protective plaque that blocks antibiotics and the immune system from getting at the infection.

Fighting bacteria with bacteria: It’s that biofilm that the living drug takes aim at.

To create their living medicine, the Barcelona team turned to Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a common cause of mild respiratory infection. An incredibly tiny bacterium, it has no cell wall and only 684 genes — perfect for reengineering. And because M. pneumoniae naturally operates in lung tissue, it should travel directly to the site of respiratory infections upon administration.

CRG director Luis Serrano pegged M. pneumoniae as a prime “living medicine” candidate twenty years ago.

Through genetic engineering, the team removed M. pneumoniae’s ability to cause disease; the resulting hollowed-out bacteria, or “chassis,” was then tested for safety in mice.

“We have developed a battering ram that lays siege to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.”

María Lluch

Little warrior in hand, the team then introduced four foreign genes — known as “transgenes” — that give the modified M. pneumoniae the ability to produce bacteria-killing and biofilm-fighting molecules and toxins.

The engineered bacteria battered through the infection’s defenses, softening it up so that antibiotics could wipe it out. In treated mice, the living drug eliminated acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, doubling their survival rate compared to untreated mice. A single, powerful dose of the treatment showed no toxic side effects in the lungs, and the mice’s immune system mopped up the friendly bugs within four days.

To further test their bacteria, the team collected P. aeruginosa biofilms from the endotracheal tubes of ICU patients, which the M. pneumoniae broke through and destroyed in lab experiments.

The team envisions their bacteria-based medicine as being administered via nebulizer, so it can be inhaled into the lungs. More tests will be needed before they can move to the clinical trial phase, however.

Although interesting, the engineered bacteria will have to clear high hurdles for toxicology before they can be used in humans.

The hurdles and hopes: While the research is interesting, getting it from the lab to patients may be “very difficult,” says Prabhavathi Fernandes, chair of the Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership.

“The idea is interesting but for it to be approved by regulatory agencies to allow testing in humans it would have to clear weeks of toxicology studies in two animal species,” Fernandes tells Freethink.

There was some inflammation noted in the Nature Biotechnology paper from only one dose, and repeated doses are likely to have a larger effect.

“I think the hurdle of clearing toxicology is a significant barrier to its use in human infections,” Fernandes says.

Another potential concern with any living organism therapy is recombination — that native M. pneumoniae, if any were present, and the engineered version may end up exchanging genetic sequences.

If the living drug were to clear those hurdles, the researchers envision stopping Pseudomonas aeruginosa as just the start for engineered bacterial medicine — theoretically, they can be outfitted to fight various pathogenic threats.

“The bacterium can be modified with a variety of different payloads – whether these are cytokines, nanobodies or defensins,” Serrano said.

“The aim is to diversify the modified bacterium’s arsenal and unlock its full potential in treating a variety of complex diseases.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.