The baby shower had been canceled; the ever crucial car seat was nowhere to be found, expectant parents Kenyatta and Derek Coleman told STAT. The couple “didn’t know we would even bring home a baby,” Kenyatta said.

Their daughter had a rare condition called a “vein of Galen” malformation: blood vessels in the fetal brain were not developing properly, joining wrong and potentially leading to brain damage, heart failure, or other organ damage.

But a surgical procedure performed in utero — the first of its kind in the US — ensured that the Colemans’ baby did make it home. Despite the severity of the condition, their daughter has been doing fine since her birth on March 17, two days after a procedure performed by a team from Boston’s Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

A vein of Galen malformation happens when a fetal brain artery connects directly to a vein, and can be fatal.

The surgical team watched her closely in the NICU following her birth, STAT reported.

“That’s when it really started hitting home that this baby was just doing great,” Darren Orbach, a neuroradiologist at Boston Children’s, told STAT. “Because all of us who care for these kids see how very sick these babies are, in the NICU, for weeks and weeks or months. And just to see her look fine, really on no medication and not in a breathing tube or anything like that, that was really fantastic.”

What is a vein of Galen malformation? A vein of Galen malformation occurs when a fetal brain artery links up directly to a vein, with no capillaries in between.

Although they both move blood around, arteries and veins have very different jobs. The artery delivers high-pressure blood containing oxygen from the heart, while veins return the blood under low-pressure. Because the mechanical stress is lower, veins have thinner walls — a huge problem if the fast-moving blood from an artery begins pumping through them.

“Over time the vein essentially blows up like a balloon,” Orbach told MIT Technology Review.

Because that oxygenated blood is being diverted before it reaches its destination, Oxford University Hospital consultant neurosurgeon Mario Ganau told Tech Review, brain damage could be caused by the resulting hypoxia. Infants with vein of Galen malformation run the risk of a brain bleed, and when they are born, the abrupt new strain on the heart can lead to heart failure.

“All of a sudden there’s this enormous burden placed right on the newborn heart,” Orbach told Tech Review. “Most babies with this condition will become very sick, very quickly.”

Because of the rapid onset of serious symptoms after birth, researchers are trying to treat the condition inside the womb, before their hearts and lungs need to stand on their own.

The surgery: The procedure, written up in the American Heart Association journal Stroke, was part of an FDA-approved clinical trial.

Because of the unusual nature of the surgery, a team from across Boston Children’s and Brigham and Women’s Hospital was assembled, including radiologists, anesthesiologists, and maternal fetal care specialists.

A Boston-based team performed an in utero surgery to treat the malformation, the first of its kind in the US.

“In every fetal surgery, there are two patients: the baby and the mother, and caring for both the fetus and the mother is an important aspect of fetal procedures,” said Carol Benson, a radiologists at Brigham and Women’s and study co-author. “You need to make sure that everything is aligned perfectly, and we couldn’t do anything without the precise communication and teamwork of everyone involved.”

In the operation, both mother and fetus were given injections to prevent pain, and to keep the fetus from moving during the surgery.

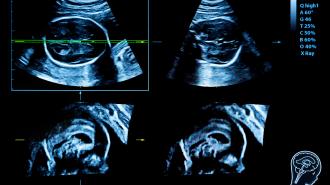

Using ultrasound as a guide, the surgeons then inserted a needle through Coleman’s abdomen, the wall of the uterus, the fetal skull, and into the vein of Galen malformation. Tiny platinum coils, delivered through the needle, were then expanded to block off the point where the artery and vein were joined. When the blood flow pattern reached a healthy point, the team quit administering coils.

Post-surgery, the doctors and parents “were thrilled to see that the aggressive decline usually seen after birth simply did not appear,” Orbach said in a statement. Since then, the Colemans’ daughter has been progressing “remarkably well.” She has required no medication and is eating normally, gaining weight, and living at home after being discharged from the NICU.

“Elegant and exciting”: The surgery was “a very elegant and exciting solution to a difficult problem,” Ibrahim Jalloh, consultant neurosurgeon at the UK’s Cambridge University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, told Tech Review.

Figuring out the risks of the procedure can only be done by studying further cases, Jalloh pointed out — which may take a while, considering the rarity of the condition. But because of the poor outcomes of newborns with vein of Galen malformations, Jalloh suspects the technique will be “the way forward.”

The Boston team hopes that, despite this being only one patient thus far, their fetal surgery technique could mark a “paradigm shift” in the treatment of vein of Galen malformation.

“This may markedly reduce the risk of long-term brain damage, disability, or death among these infants,” Orbach concluded in a statement.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.