Not the sole province of nuclear power plants and doomsday plots, uranium is having a direct impact on human lives.

Uranium contamination — whether from human pollution or leaching into groundwater from rocks and soil — can render water undrinkable and dangerous, causing kidney toxicity and increasing the risk of cancer.

But MIT researchers have developed a possible solution: a spongy water filter that sucks the heavy metal out of the water, taking it from polluted to potable in hours.

In the U.S, “many areas are affected by uranium contamination, including the High Plains and Central Valley aquifers, which supply drinking water to 6 million people,” Ahmed Sami Helal, a postdoc in MIT’s Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering, said.

Uranium contamination also exacerbates water access issues in the Navajo Nation, where it bleeds into aquifers and surface water.

Water in many areas of the US is affected by uranium contamination.

“Even small concentrations are bad for human health,” Ju Li, professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT, said.

Their potential fix harnesses the second hottest thing in material science: graphene.

Sponging out uranium contamination: As the name suggests, graphene is made from the same material as graphite, the soft stuff inside your pencil.

But, only one atom thick, graphene has some bizarre characteristics, including incredible strength, strong electrical capabilities, and flexibility — all of which makes it a hot topic of research, and earned its discoverers, Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, the Nobel Prize in 2010.

For their water filter experiment, published in Advanced Materials, the MIT team whipped up a graphene oxide foam, which they shot an electrical charge through. That charge split up the water molecules around the foam, which in turn raised the pH, making the water around the foam more acidic.

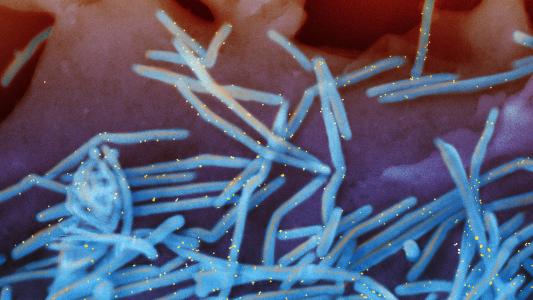

That acidic environment created a chemical reaction that sucked the uranium particles out of the water, where they glommed onto the surface of the graphene foam and formed crystals.

The re-usable foam filter sucked uranium particles right out of the water, making it safe within hours.

“Each time it’s used, our foam can capture four times its own weight of uranium,” Li said, and it pulls out more of the heavy metal than other uranium decontamination methods per gram. It also cleans up quickly.

“Within hours, our process can purify a large quantity of drinking water [to] below the EPA limit for uranium,” Li said.

A heavy burden: The team aimed to find a better way of eliminating not only uranium contamination but also other heavy metals, including lead, mercury, and arsenic.

Current techniques are poor at separating out the pollutants, Helal said. “So they involve long operation times, high capital costs, and at the end of extraction, generate more toxic sludge.”

Uranium contamination proved an ideal test: EPA testing has revealed that uranium levels are ticking up in reservoirs and aquifers in the Northeast, leaching from natural rocks, while old mines may be leaking into the waters of the West.

The filter can be tweaked to filter out other heavy metals like mercury, lead, and cadmium.

The team’s method is reusable, as well. Those uranium crystals — which resemble fish scales — flake off when the electrical charge is reversed, leaving a clean graphene sponge ready to be used again. The filter is “a major breakthrough in reusability, because the foam can go through seven cycles without losing its extraction efficiency,” Li said.

Low cost and effective, the researchers picture their device eventually being able to remove uranium contamination right at people’s taps, or being chemically tweaked to filter out other pollutants.

“There is a science to this, so we can modify our filters to be selective for other heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium,” Li said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.