An Alzheimer’s trial, spearheaded by the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, is not just testing a drug — it’s also putting the leading theory behind the disease, the amyloid hypothesis, on the line.

The amyloid hypothesis: The frontrunner theory about what causes Alzheimer’s disease hangs its hat on a protein called beta-amyloid, a sticky compound that can accumulate in the brain.

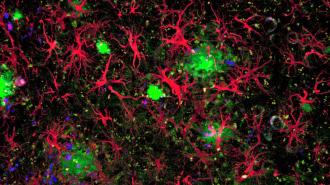

Alzheimer’s signature biomarker is the presence of clumps of amyloid, called plaques, as well as “tangles” of another protein, called tau, in the brain.

In the amyloid hypothesis, the buildup of plaques chokes off communication between neurons and causes inflammation, which in turn kills brain cells — causing cognitive decline.

An Alzheimer’s trial is not just testing a drug — it’s also putting the leading theory behind the disease, the amyloid hypothesis, on the line.

But although it’s garnered the most support, attention, and resources, the amyloid hypothesis does have one big problem: reducing beta-amyloid buildup in the brains of people has yet to cure anyone of Alzheimer’s. Many drugs have succeeded in breaking up or preventing amyloid plaques from forming, but few, if any, show signs of slowing the disease down.

After decades of failure, other hypotheses — including tau and, a bit further afield, a role for viral infections — have begun to garner more interest.

The new Washington University study may help put the question to rest.

“Many of us think of that as the ultimate test of the amyloid hypothesis,” Washington University neurology professor Randall Bateman told NPR.

“If that doesn’t work, nothing will work.”

The study: The trial, the DIAN-TU Primary Prevention trial, is based on evidence showing that beta amyloid accumulation begins years before dementia symptoms do.

This may open up a window to treat the disease before it starts causing brain damage — what the researchers refer to as “primary prevention.”

According to NPR, the four-year study is looking to enroll 160 people whose families have dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. This rare form of Alzheimer’s, known to be caused by inherited mutations, can strike people as early as their 30s and 40s.

In the amyloid hypothesis, the buildup of beta-amyloid plaques chokes off communication between neurons and causes inflammation, which in turn kills brain cells — causing cognitive decline.

“The earliest they can come in is 25 years before we anticipate they would start to develop symptoms,” Eric McDade, who will oversee the experiment, told NPR. “For most of these families, that actually puts them in their mid 20s when we’re going to start this trial.”

The placebo-controlled trial will test an anti-amyloid antibody called gantenerumab, given to patients preemptively before they start to show amyloid buildup.

“What we’re trying to do is to prevent that amyloid pathology from developing in the first place,” McDade said.

The team will follow the volunteers to see if their drug helps prevent or slow amyloid buildup compared to the placebo, and, if so, whether that prevents other signs of Alzheimer’s from developing — putting the amyloid hypothesis to the test.

“If we prevent amyloid pathology from developing and these other markers continue to develop and unfold, this would be one of the best ways to say, listen, amyloid is really not what we should be targeting,” McDade said.

Adhering to the amyloid hypothesis: Finally understanding the value of targeting amyloid could have major implications for Alzheimer’s prevention, treatment, and research. The lion’s share of drugs in development take aim at the protein, including Biogen’s controversial Aduhelm, which is also an antibody.

It was approved by the FDA — despite the misgivings of prominent researchers and the FDA’s own advisory panel — based on its ability to clear the protein alone, not for improving cognition. The approval seemed based on the assumption that the amyloid hypothesis is the right one.

The amyloid hypothesis has a problem: reducing beta-amyloid buildup in the brains of people has yet to cure anyone of Alzheimer’s.

But the long list of failed, disappointing, or murky trial results — including for gantenerumab — could perhaps be partially explained by giving the drugs only after it’s too late.

Treating patients who are almost certain to develop Alzheimer’s before plaques begin to build up in their brains will give anti-amyloid drugs their best shot at preventing the disease.

“My prediction is it will work, and it will work fantastically,” Bateman told NPR. “If we can really prevent the plaques from starting and taking off and those downstream changes from going, my prediction is these people will never get Alzheimer’s.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.