Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and US and EU sanctions, western companies began a steady withdrawal from Russian markets. Microsoft was no exception, and in June, the company blocked Russian users from downloading the latest versions of Windows – impacting the roughly 95% of computers and laptops that currently run on Windows.

This may not seem like a particularly drastic move to the average Windows user in Russia – who at least in the short term, won’t be hugely impacted by a loss of remote support from Microsoft, or official updates for Windows 10 and 11.

Microsoft blocked Russian users from downloading the latest versions of Windows in June 2022.

Yet the move could have far more wide-reaching implications for companies and government agencies. Crucially, these groups are responsible for running a diverse array of everyday commercial and public-facing systems: from elevators and cash registers to medical devices and industrial machinery.

To boost its resilience in the face of this mounting problem, the Russian government has now announced plans for switching from Windows to Linux, a free and open-source operating system.

The announcement: On September 20, the Russian daily newspaper Kommersant reported that the Ministry of Digital Development was preparing new changes to policies on software products.

While these changes won’t be imposed directly, the ministry states that in order to receive preferences in tax benefits, as well as government contracts, companies offering software products will be required to switch to Linux-based operating systems. To make this switch, companies would need to rebuild many of their products virtually from scratch.

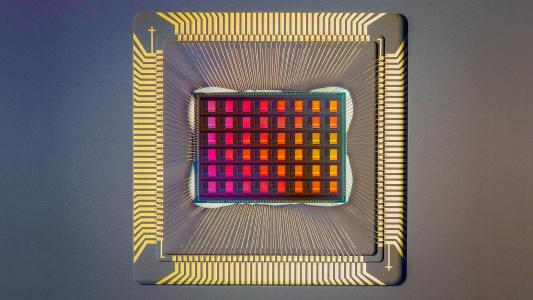

Because Linux is free and customizable, it is more flexible and can run far better on older computers.

At this stage, it is far from clear how they will handle such monumental logistics – but already, leading figures in several Russian software companies have weighed in. Talking to Kommersant, Aleksey Smirnov of Basalt SPO, a company specializing in software security, suggested that the requirement should be introduced in stages for different classes of software.

Under Smirnov’s proposal, easier-to-switch software products could be pressured to switch over almost immediately, while more complex systems, such as data protection and office management databases, could be introduced in Linux after around 2 years.

The benefits: The potential advantages of this plan have been highlighted by some in the Russian software industry. First and foremost, Linux is free and customizable. This not only makes it more flexible, it also means that Linux can run far better on older computers, without the need for costly hardware upgrades.

The switch may be a fundamentally important step towards a “full-fledged domestic IT ecosystem” in Russia.

Natalya Selina

Mikhail Lebedev, at the office software developer Almi Partner, argued that the switch wouldn’t require particularly heavy investments or development times. His prediction is that around 10% of software products would require a full rebuild.

For Natalya Selina at the Linux-based Astra operating system, the switch may be a fundamentally important step towards what she calls a “full-fledged domestic IT ecosystem” in Russia.

Yet despite such optimistic predictions, the changes proposed by the Ministry of Digital Development will inevitably face numerous challenges – making their success a far from certain outcome.

The roadblocks: Perhaps the most pressing issue with the plan is that the number of Russian software developers specialized in Linux-based operating systems number just a fraction of those who have only ever worked with Windows. This is a particularly daunting prospect for developers whose products will need to be built entirely from scratch.

Some of the systems that will require complete rebuilds are foundational to Russia’s economy.

Rustam Rustamov

Dmitry Komissarov at New Cloud Technologies, which develops an alternative to Microsoft Office, admitted to Kommersant that the feat of rebuilding his company’s products on Linux-based operating systems would be comparable in time and investment to the efforts of the developers who built Microsoft’s original Office suite.

Rustam Rustamov at the Red Soft operating system added that some of the systems that will require complete rebuilds are foundational to Russia’s economy. These include banking systems, which have now been written for Windows for decades.

This ultimately means that even tighter restrictions may not be enough to encourage software developers to make the switch, and will do little to boost the resilience of Russia’s faltering tech economy.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.