It is a disaster difficult to imagine, a biblical plague, a food-devouring black cloud of legs and wings, antenna and mandibles. A locust swarm can devour billions of dollars worth of crops, plunging a region immediately into famine; little wonder they were wielded as a divine Old Testament weapon.

Now, a group of researchers (headed by Le Kang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences) has identified the pheromone they believe causes the locust swarm to form out of previously mild-mannered grasshoppers — and it may prove the key to capturing locusts or even preventing the swarm in the first place.

Famine on the Wing

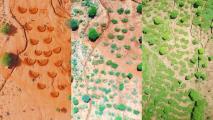

A locust swarm — bands of which marauded across East Africa this summer — is a veritable cyclone of insects, potentially spanning 100 square miles or more; per NPR, there can be 40-80 million locusts packed into each square half mile.

Far from a localized threat, a locust swarm can move vast distances, over 60 miles a day, leaving ruined fields in their wake.

Locusts are a gregarious, gluttonous type of grasshopper. Periodically, they have the ability to alter their forms — turning black, among other anatomical changes — and begin producing pheromones that lead to them to assemble into the Megazord of a locust swarm.

Those swarms then start their ravenous rovings; according to National Geographic, a mighty locust swarm may devour up to 300 million pounds of crops — in one day.

They’re flying famines.

Stopping the Locust Swarm

Stopping a locust swarm is exceedingly difficult once they get going.

“They are powerful, long-distance flyers, so they can easily go a hundred plus kilometers in a 24-hour period,” the Arizona State University Global Locust Initiative’s Rick Overson told NPR.

“They can easily move across countries in a matter of days, which is one of the other major challenges in coordinated efforts that are required between nations and institutions to manage them.”

Le Kang’s research team has identified the pheromone that triggers the swarming behavior. Called 4-vinylanisole (4VA), it is an aggression pheromone in the migrating locust. Regardless of sex or age, locusts are attracted to 4VA, the authors wrote in the paper, published in Nature,

The researchers found that it can only take four or five locusts to spark 4VA production and ignite a locust swarm.

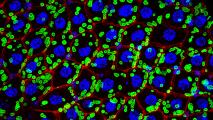

They also discovered how the locusts are sensing the call to pillage: through their antennae.

When the specific site on the antenna that senses 4VA is removed — thanks to the genetic X-acto knife CRISPR-Cas9 — the locusts could no longer sense the pheromone and did not switch to swarm mode.

The Upshot

Armed with this trigger, we may now be able to develop new tools to try and curb, or even prevent, a locust swarm’s formation. Traps laced with 4VA could potentially draw the insects in while they are still in their solitary phase, although, as Gizmodo points out, you’d need a lot of traps to make a dent in swarms that can be millions strong.

On the more extreme end of solutions, identifying the genetic mutation which can remove the locust’s ability to sense 4VA opens up the possibility of using a gene drive. Gene drives cheat the 50/50 genetic odds of sexual reproduction, pushing genes that scientists select throughout an entire population.

In theory, we could create entire populations of locusts who can no longer sense 4VA — or even just kill them all. Such a move could not be undergone lightly, however; tampering with an entire species promises to present complex problems and potentially unintended consequences.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.