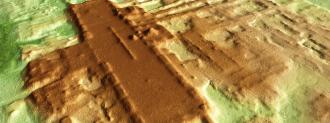

Cloaked in copses of trees, hidden beneath a quilt of greens and browns, a massive structure of the Mayan civilization, sleeping in plain sight for centuries, has been found in Mexico, National Geographic reports.

The complex was discovered in 2017 by LiDAR, at a site called Aguada Fénix, in Mexico’s Tabasco state, but announced in a paper published in Nature June 3. LiDAR uses airborne lasers to reveal structures below dense foliage; sometimes called the “El Dorado Machine,” it is revolutionizing archeology.

Dated to 3,000 years ago, the complex sits in what is known as the Maya lowlands, from which the Mayan civilization sprung. It is the most ancient and enormous structure found in the Maya region, so immense its height is hidden.

“It’s fairly hard to explain, but when you walk on the site, you don’t quite realize the enormity of the structure,” Takeshi Inomata, an archeologist at the University of Arizona and lead author of the paper, told National Geographic.

“It’s over 30 feet high, but the horizontal dimensions are so large that you don’t realize the height.”

Nine causeways lead to the artificial plateau, which is crowned with structures, including a 13-foot pyramid. The platform and buildings are estimated to encompass 130 million cubic feet, dusting even the most massive of Egypitan pyramids.

Inomata estimates it would’ve taken 5,000 workers six years — full-time, nonstop — to build it. But it may also have been built over a long period of time.

The discovery is strong evidence of a newly developing theory: that the earliest constructions of the Mayan civilization were even larger than those from the Classic Maya period, the span from 250-900 A.D. when the empire was exerting its influence across Mesoamerica.

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal from the site estimates that it began to be built in 1,000 B.C. With no older buildings in the region, archaeologists theorize that these people, precursors to the Classic Mayan civilization, had a nomadic lifestyle — making the mighty structure all the more intriguing.

Inomata theorizes that the sheer size of the structure is a clue that these people were leaving their hunter-gatherer life behind.

Not all archeologists agree that this points to the first step towards settling down, however.

“Monumental constructions by pre-sedentary people are not uncommon globally,” Terracon Consultants Inc. archeologist Jon Loshe told National Geographic. Loshe was not involved with the study.

Also up in the air? What the site actually was. Inomata thinks it was possibly a ceremonial center, where people could gather for religious rituals.

Inomata and Loshe both speculate that the site is evidence for egalitarian cooperation that Loshe believes was typical of the early Mayan civilization. A collection of jade axes may have symbolized the end of the project, while some of the soil was laid in a checkerboard pattern.

The large platform got higher and smaller as the Mayan civilization evolved, Inomata says; eventually, the top of the pyramid had only room for the elite.