Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a therapy that sends mild electric current through your brain; it’s a well-known and widely used treatment for patients with depression, traumatic brain injuries, or neuromuscular disease. And while this treatment is typically administered in a lab, under the watchful eye of a clinician, it’s becoming more and more common to find a tDCS device for sale online.

But not all physicians believe this should be the case. While such devices have been approved in the UK and EU for at-home treatment of depression, in the U.S., they do not have FDA approval and have been branded as catch-all “wellness” devices instead.

Ultimately, whether these devices end up on drug store shelves or remain sequestered in research labs will not be the sole decision of the FDA, says Marom Bikson, professor of biomedical engineering at City College of New York, but also the companies who choose to innovate the technology.

The Science of Stimulation

Not to be confused with another form of neurostimulation, electroconvulsive therapy (formerly known as electroshock therapy), tDCS is a much milder form of electrical stimulation. While electroconvulsive therapy induces seizures in patients to provide treatment, patients using tDCS devices often only experience a small tickle.

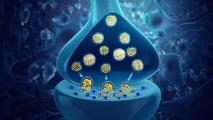

As its name might suggest, tDCS works by applying a sustained, mild direct current to specific parts of a patient’s brain through electrodes. In a doctor’s office, this device might take the form of a wired shower cap, but in at-home devices, it looks a little more like a headband. Regardless of its shape, the current stimulates neural activity in the brain and can increase the firing of neurons. In patients suffering from depression, who may have fewer neurons firing in certain parts of their brain, a treatment like this can help increase brain activity.

As a treatment for depression, tDCS is often sought as an alternative to antidepressants — and the potential side-effects that come with them. Side-effects for doctor-administered tDCS treatments have been extremely minimal, thus far, generally appearing in the form of warmth or slight discomfort during the treatment.

tDCS is often sought as an alternative to antidepressants and the potential side-effects that come with them.

However, when it comes to electric stimulation alternatives to antidepressants, there’s also another name in the game: transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). More similar to tDCS than electroconvulsive therapy, TMS uses a magnetic induction to directly stimulate the activity of neurons in the brain. But unlike tDCS, these devices are bulky, have a stronger current, and are applied for a shorter time.

Also unlike tDCS, TMS therapy is FDA-approved.

However, Tracy Vannorsdall, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins Medical School, says that the portability of tDCS devices still makes them a more appealing candidate for at-home solutions.

“TDCS devices are less technically complex and, in fact, often run off of 9-volt batteries,” says Vannorsdall. “They are light, portable, and relatively inexpensive, which has contributed to their popularity and the interest in developing at-home tDCS devices. In contrast, TMS devices are more complex, expensive, and immobile, which has largely limited this treatment to the clinic.”

“Wellness” Meets Wellness

Vannorsdall says that TMS’s FDA approval is not so much a comment on the safety and efficacy of tDCS devices (or a lack thereof) but instead a testament to how rigorously TMS treatments have already been tested.

“TMS has been extensively studied and approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of depression,” she says. “In contrast, while tDCS remains investigational from an FDA standpoint, the tDCS devices themselves are relatively simple, low cost, and portable. These factors, in combination with its good safety profile, has led to a strong interest in the development of tDCS devices that can deliver treatment in people’s homes.”

Despite a growing number of reports demonstrating tDCS’s effectiveness as a treatment for depression and other disorders, the devices still lack enough evidence to tip the FDA’s scale toward clinical clearance. While this hasn’t stopped companies from marketing these devices, it has restricted how they can market them. Instead of specifically treating depression, tDCS devices on the U.S. market are focused on “wellness” approaches to brain stimulation, such as improving memory or cognition.

“(These devices) are relatively one-size-fits-all, and not necessarily fitted to the anatomy or target problem of a particular individual,” says Vannarsdall.

A Path Forward Across the Pond

For the Swedish company Flow Neuroscience, this isn’t the case. Approved in the UK and EU as a “safe and effective medical device to use at home,” the company’s at-home tDCS treatment for depression is showing what a path forward for these devices might look like.

“The Flow treatment comprises a brain stimulation headset and an app therapy programme,” says Flow Neuroscience co-founder and clinical psychologist Daniel Mansson. “We combine these treatment methods because we believe that treating both the biology and the psychology of the user is necessary to efficiently treat depression and prevent it from returning.”

tDCS devices stand poised to increase patients’ flexibility and autonomy when it comes to depression care.

Mansson says that Flow, which launched at the end of 2019 and costs about $500 per headset, works by using tDCS stimulation on a part of the frontal lobe called the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex — an area often associated with depression and low neural activity. Flow recommends users complete two to three sessions with the headset per week for about 30-minutes each.

Also unique to Flow is its AI-driven (and psychologist created) app, which is designed to provide users behavioral therapy to help them maintain a positive headspace after the treatments.

Mansson says that the technique used in the Flow headsets is the same technique that randomized trials have shown to be as effective as traditional antidepressants. However, Mansson says that the team does not yet have conclusive results from the Flow devices themselves, but should have more significant data to share by the end of April 2020.

Two Views for The Future

Regardless of Flow’s results, says City College’s Marom Bikson, tDCS treatments will never be foolproof.

“Everything depends on patient to patient,” he says. “For every patient who sees a doctor, the doctor’s job is to pick a therapy and titrate (adapt) that therapy to the patient. With neuromodulation, that should be the case as well. But we’re still learning how to do that, and how best to personalize it.”

But that shouldn’t necessarily be a reason to discourage the use and developments of these devices either, says Bikson.

“So many patients, or family members, are the advocates of their own health care, and they’re looking for something beyond what their physicians have available.”

tDCS devices like Flow stand poised to increase patients’ flexibility and autonomy when it comes to depression care, but Bikson and Johns Hopkins’ Vannorsdall represent two sides of a divide when it comes to how they should be pursued.

Bikson believes there’s no reason tDCS devices like Flow couldn’t one day be sold on the shelves of CVS.

“I do worry about at-home stimulation using retail tDCS devices when there is no input or guidance from a professional about the individual user’s appropriateness for the intervention,” says Vannorsdall. She instead encourages those seeking treatment to first look for at-home — but physician-guided — tDCS studies being done in their area.

As for Bikson, he’s a little less concerned about how strict supervision would change the devices’ overall safety and efficacy.

“There’s different levels of medical supervision,” he says. “It ranges all the way from video conferences every single session to you going to your doctor’s office, pick(ing) it up, and you call him back after a month (to) tell him how it’s going.”

Bikson believes there’s no reason that tDCS devices like Flow couldn’t one day be sold on the shelves of CVS, the same way the stores sell electric stimulation for back pain — and the moment has never been better for this to happen.

“Clinical trials are ongoing,” says Bikson. “But ultimately impacting whether patients see it or not, you have commercial and regulatory factors that can be a bit orthogonal to the scientific and medical… There’s more companies and bigger companies that are getting involved in the space that are willing to make that investment. All those three things are marching forward right now, faster than they ever have before.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated from an earlier draft which incorrectly referred to Flow as a UK company. It is a Swedish company. This updated version also states that it is approved for use not only in the UK but the EU, too.