The northern white rhino reproduces like most mammals: a male and a female have sex, the female gets pregnant, and about 18 months later, a new rhino calf is born.

But right now, there aren’t any male northern white rhinos — the last one, Sudan, died in 2018 — and just two females remain.

In the past, that would mean the species’ total extinction was just on the horizon.

Today, though, teams of researchers are exploring three different plans to revive the northern white rhino — and one involves a controversial technique that could also revolutionize human reproduction.

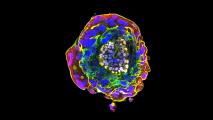

Northern White Rhino Embryos

The first plan for saving the northern white rhino is straightforward, science-wise: in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Prior to his death, Sudan lived at Ol Pejeta Conservancy, a protected wildlife area in Kenya, along with the only remaining females of his species, Najin and her daughter Fatu.

They hope to inseminate the potential mothers before 2022.

When Sudan and four other males were still alive, Ol Pejeta researchers collected samples of their sperm. They’ve since used some of that sperm to fertilize eggs they retrieved from Najin and Fatu in 2019.

This has resulted in five viable embryos.

Both Fatu and Najin have known reproductive issues that would prevent them from being able to carry a calf to term, so researchers plan to use female southern white rhinos — a close relative of the northern white rhino, with numbers in the ten thousands — as surrogates.

Their hope is to complete the insemination of the potential mothers before 2022.

However, no one knows for sure whether the pregnancy will take, as rhino reproduction is complicated. The first southern white rhino conceived through artificial insemination was only just born in July 2019, and no one has been able to produce one through IVF yet.

Hybrid Embryos

Southern white rhinos are also at the center of another plan to save their close relatives from extinction.

The procedure researchers developed to extract eggs from Fatu and Najin required the use of a risky anesthetic, so before subjecting the pair to it, they tested the technique on 12 southern white rhinos.

They then used sperm from northern white rhinos to fertilize some of the eggs they collected.

If any calves were born from those hybrid embryos, they’d be half northern white rhino and half southern, which would keep the former species somewhat alive.

Still, Fatu and Najin would be the last fully northern white rhinos, and their deaths would bring about the species’ permanent extinction — unless scientists go to Plan C, a very experimental (and sometimes controversial) technique called in vitro gametogenesis (IVG).

In Vitro Gametogenesis (IVG)

In addition to collecting sperm and eggs from the last northern white rhinos, researchers have also collected and frozen tissue samples from about a dozen members of the species.

In 2011, a group at Scripps Research Institute in California proved it was possible to create induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) from this rhino tissue. These cells can be prompted to grow into any type of specialized cell under the right conditions — including reproductive cells.

In theory, researchers could prompt northern white rhino cells to develop into sperm and eggs, fertilize the eggs with the sperm, and then implant the embryos into surrogates (like the southern white rhinos).

Researchers have actually used IVG like this to successfully impregnate mice.

If it works in rhinos or other animals, it could bring whole species back from extinction (assuming you had enough tissue samples and a surrogate mother species).

If scientists can make it work in humans, it would completely change the parameters for reproduction. Single people could have babies related only to them, creating their own eggs and sperm, and same-sex couples could have tots that are related to them both (though two men would need to find a surrogate to carry the baby).

Again, IVG has only been shown in mice so far, so the use of such an experimental technique in rhinos would likely be years down the line (and humans even further).

However, it does offer hope that the northern white rhino species doesn’t have to die with Fatu and Najin, even after their last egg is gone.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.