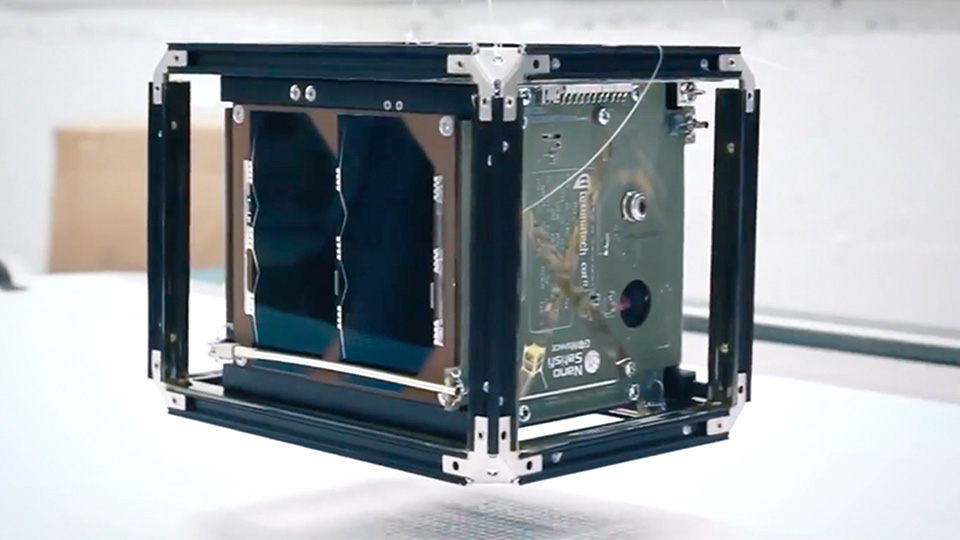

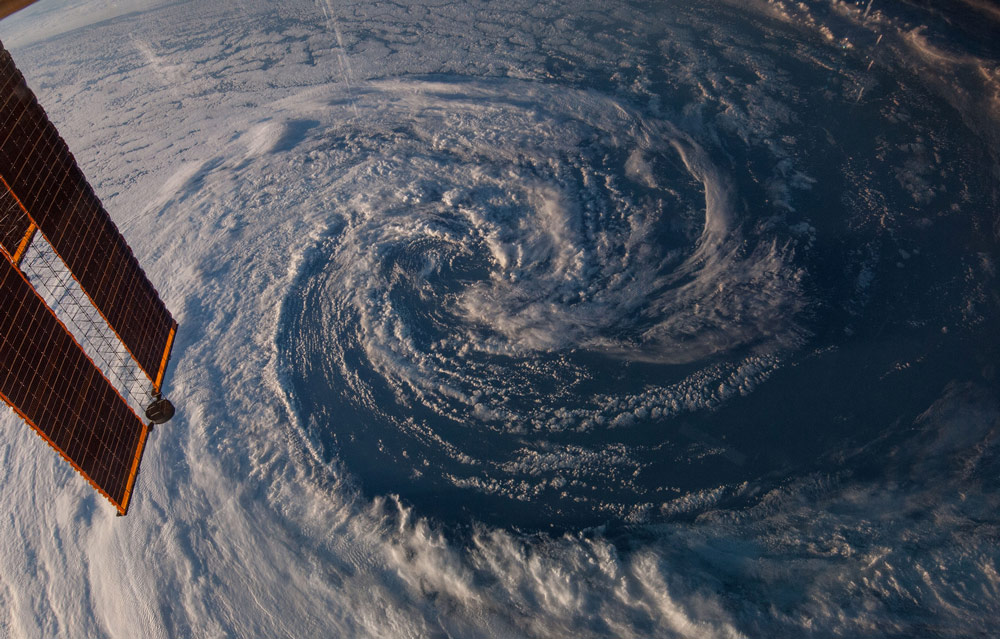

Flocks of CubeSats (like the kind we profiled in this video) could dramatically improve the way we prepare for extreme weather events: Flood-causing rain storms, power outage-inducing winds, road-closing snow storms, and deadly heat waves.

But in order for the next generation of low-cost satellites to improve the impact that this data has on our lives, we’ll need to take extreme weather forecasts more seriously. Because a lot of people simply don’t.

Psychologist Susan Joslyn at the University of Washington’s Decision Making With Uncertainty Lab studies the way weather forecasts are perceived by their intended audiences. In a 2010 survey, Joslyn and a colleague found that residents of the Pacific Northwest assumed deterministic weather forecasts were unlikely to be perfect predictions.

What’s a deterministic weather forecast? That’s when your local TV anchor tells you what the temperature is going to be at a given time that day or the next: “It’s going to be 85 and sunny at noon,” he might say. Or, “Rain will start about 6 p.m.”

Participants in Joslyn’s study assumed some error in pretty much every deterministic forecast…

Participants in Joslyn’s study assumed some error in pretty much every deterministic forecast; they suspected less error when the forecast predicted seasonally appropriate weather; and way more error when the forecast was for extreme weather like high wind or snowfall.

Joslyn posited a number of possible explanations for why respondents tended to believe forecasts that reflected climatological norms for their region (perhaps respondents believed forecasts that told them to expect rain because they live in a region that sees roughly 155 rain days a year). But she was far more interested in the fact that study participants were most skeptical when a deterministic weather forecast predicted extreme weather.

“Participants systematically discounted (extreme weather) forecasts, potentially reducing the perceived urgency for precautionary action when it is most important.”

“Participants systematically discounted (extreme weather) forecasts, potentially reducing the perceived urgency for precautionary action when it is most important.”

So Joslyn followed up her findings with another study in 2015, in which she further explored why we tend to give the side-eye to dire weather predictions. Her goal was to figure out if a high number of false alarms–dire predictions that proved to be wrong–”led to a decrease in compliance with the advice.”

She found that “(p)articipants were less likely to follow advice…and made economically inferior decisions when the advice led to more false alarms.” But she also found “no evidence suggesting that lowering false alarms increased compliance significantly.”

So how do we improve trust in weather forecasts?

If we take precautions for extreme weather, as many residents of the northeastern U.S. did when forecasters predicted historic snowfalls in January 2015, and nothing bad happens, we get irritated. But when governments and forecasters hedge in the opposite direction–as Atlanta did in 2014–the results can be even worse. The ice storm that Atlantans thought would only brush their city ended up stranding tens of thousands of motorists on the road for more than 12 hours.

The best way to build trust, Joslyn told TIME in 2015, is to introduce probability statistics into forecasts. “What authorities ought to do for decision makers and the public is tell them ‘yes, I think there’s a good chance’, and then tell them the probability. What they tend to do is say ‘It’s going to happen or ‘It’s not going to happen.’ Our research indicates that giving the full story has the best results.”

And with a CubeSat revolution underway, giving the full story will be easier than ever. Watch the video below for more.