A new peanut allergy treatment based on mRNA could potentially lead to therapies that prevent all types of allergies — and maybe even reverse autoimmune conditions like type 1 diabetes.

The challenge: Our immune system helps us stay healthy by attacking foreign invaders, such as disease-causing viruses and bacteria. Sometimes, it attacks harmless invaders, too — this is what’s happening when a person experiences an allergic reaction to something typically benign.

Peanuts are one of the most common allergens — an estimated 1 in 50 children is allergic to the legumes, and while some experience only mild reactions, such as hives or nausea, exposure to peanuts can be life-threatening for others, causing anaphylaxis.

The only approved peanut allergy treatment takes several months to kick in and must be taken daily for life.

Studies show that early exposure to peanuts helps reduce the risk of developing an allergy, but even then, some kids will still become allergic. About 20% of children who do develop a peanut allergy will outgrow the condition, but it’s lifelong for the rest.

The only FDA-approved peanut allergy treatment takes several months to kick in and must be taken daily for life. It also doesn’t actually stop patients from having allergic reactions to peanuts — it just minimizes the risk of a severe reaction.

What’s new? Researchers at UCLA have now used mRNA — the type of molecule used in the highly effective COVID-19 vaccines — to develop a treatment that could not only prevent a severe allergy from developing but could even reverse signs of a peanut allergy in mice.

“As far as we can find, mRNA has never been used for an allergic disease,” said André Nel, co-corresponding author of the team’s study, which has been published in ACS Nano.

The mRNA was encoded with instructions that tell cells how to create the peanut allergy epitope.

The background: In a previous study, the UCLA researchers identified a specific fragment of a peanut protein — known as an “epitope” — that alleviated peanut allergies in mice when delivered directly to their livers using a nanoparticle.

It appears this is due to the liver’s antigen-presenting cells, which train the immune system to tolerate foreign proteins.

“If you’re lucky enough to choose the correct epitope, there’s an immune mechanism that puts a damper on reactions to all of the other fragments,” said Nel. “That way, you could take care of a whole ensemble of epitopes that play a role in disease.”

The upgrade: For their new study, the UCLA researchers encoded mRNA with instructions that tell cells how to create the peanut allergy epitope — this mirrors how mRNA is used in the COVID-19 vaccines to train cells to create bits of the coronavirus’ spike protein.

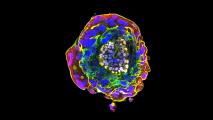

They then put the mRNA in the nanoparticle. This was easier than actually loading the peanut protein epitope itself into the particle, and it opens the door to including multiple epitopes in a single nanoparticle in the future, which might be necessary if the technique is used to treat other types of allergies.

Finally, they added a sugar molecule to the surface of their nanoparticle to help it bind to the liver’s antigen-presenting cells.

The new treatment had increased the animals’ tolerance to peanut protein.

The results: To test the new peanut allergy treatment, they administered it to mice in two doses a week apart. For comparison, other groups of mice got either no treatment, the treatment without the added sugar protein, or the nanoparticle filled with mRNA that didn’t code for anything.

A week later, they fed the mice a peanut protein extract that made them sensitive to peanut allergens. A week after that, they challenged the mice with enough peanut protein to trigger anaphylaxis, and the group treated with the sugar nanoparticle treatment had the least severe reaction.

This suggested that the therapy could prevent the development of a severe peanut allergy.

“We believe [our platform] may be able to do the same for other allergens, in food and drugs, as well as autoimmune conditions.”

André Nel

To see if it could potentially treat people who are already severely allergic to peanuts, the team performed the experiment again, but this time, they made the mice sensitive to peanut allergens before administering the nanoparticles.

Again, the sugar nanoparticle led to the mildest symptoms during the allergen challenge, and mice treated with particles containing epitope-encoding mRNA experienced “far milder symptoms” than ones in the comparison groups.

By analyzing the levels of certain antibodies, enzymes, and other substances, the researchers were able to confirm that the new treatment had increased the animals’ tolerance to peanut protein — essentially reversing their peanut allergies.

Looking ahead: If all goes well in additional lab testing, the UCLA scientists believe their peanut allergy treatment could be ready for human clinical trials in about three years.

Looking further ahead, they envision the same system being used to treat or prevent other allergies, and maybe even help people overcome type 1 diabetes — other researchers have already identified the epitopes that trigger the immune system to attack the cells that produce insulin in that condition.

“We’ve shown that our platform can work to calm peanut allergies, and we believe it may be able to do the same for other allergens, in food and drugs, as well as autoimmune conditions,” said Nel.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.