We’ve sent many thousands of objects into space since the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 in 1957. Ranking those objects in order of weirdness might seem like a Herculean task, but it’s not. The general rule is that if it seems weird on its face, it’s actually not. Like, some folks think it’s weird that U.S. Astronaut John Young smuggled a corned beef sandwich on the Gemini 3 mission, but when you think about it, astronauts have to eat and corned beef is delicious. The same goes for human ashes . To my mind, it is actually less weird to send a person’s remains into space than it is to pump them full of preservatives, dress them up like a mannequin, and bury them under six feet of dirt.

To that end, here are the four actual weirdest things we’ve sent into space:

4) A golden record that is full of lies

I don’t know if there’s intelligent life elsewhere in the universe, but if there is, I’m almost certain they won’t know what to do with the gold-plated copper records affixed to Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. Launched in 1977, the two unmanned vessels were sent out into space as greetings to whatever intelligent life might exist in the universe. Each record is inscribed with a series of sounds (animal calls, ocean surf), 90 minutes of various types of music, and greetings from U.N. Secretary General Kurt Waldheim and U.S. President Jimmy Carter. The records are also inscribed with picture-based instructions and images encoded in analog format. You can listen to Secretary Waldheim’s greetings to the cosmos here:

The Voyager records were the brainchild of astronomer and astrophysicist Carl Sagan, who saw them as a means to communicate Earth’s peaceful intentions and stunning biodiversity. The Voyager spacecraft left our solar system roughly 26 years ago, and won’t reach another planetary solar system for 40,000 years.

This is an incredibly weird thing to send into space, even if you optimistically assume that both Voyagers will survive floating through space for the next 40 millenia (they could be destroyed by asteroids).

What if the other intelligent life forms in the universe don’t interpret vibrations in the air the same way we do? Like, they might not even be able to hear. What if they don’t have eyes? What if–and I’m just spitballing here–the intelligent life form that discovers the records is incredibly aggressive? The records we sent into space four decades ago make humans sound like pacifists and Earth like a buffet.

But let’s assume they’re peaceful; that they’ve evolved past intra-species violence and no longer use or even develop weapons. While the Voyager records represent everything good and right about humanity on two discs (which you can actually buy in remastered form), they are essentially a big lie. Yes, Earth is great (I honestly have no desire to live anywhere else) and many people living here would be thrilled to establish peaceful relations with another intelligent species. But we’re not a perfect species, and the Voyager records could probably use a disclaimer. Something along the lines of, “If you decided to visit, please don’t surprise us. We have a tendency to blow things up.”

3) Evidence of our own inferiority

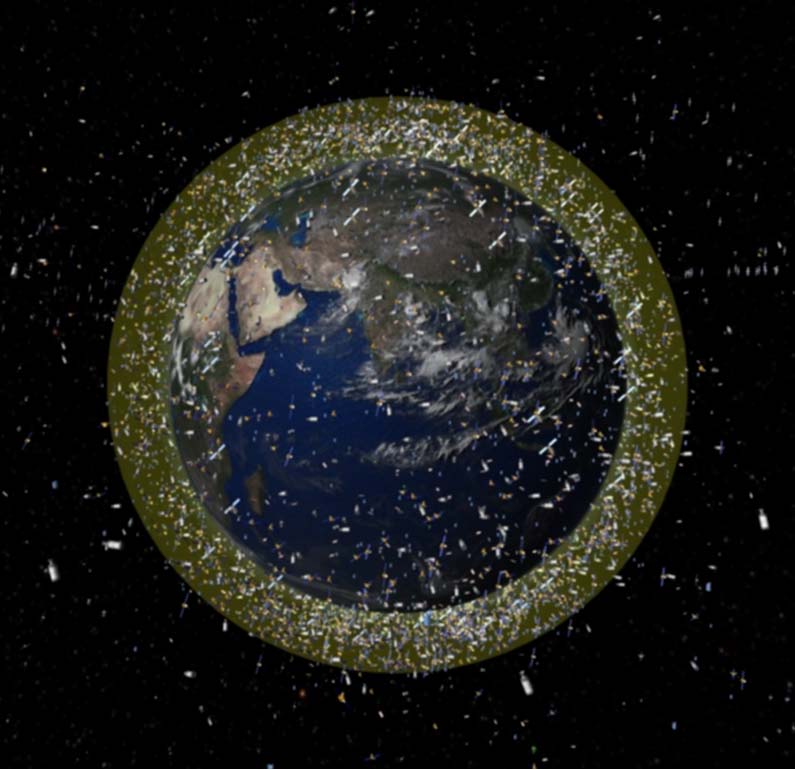

You can’t see it from wherever you are right now, but the Earth is surrounded by garbage.

“Inactive satellites, the upper stages of launch vehicles, discarded bits left over from separation, and even frozen clouds of water and tiny flecks of paint all remain in orbit high above Earth’s atmosphere,” according to Space.com. “Over 21,000 pieces of space trash larger than 4 inches (10 centimeters) and half a million bits of junk between 1 cm and 10 cm are estimated to circle the planet. And the number is only predicted to go up.”

The trash doesn’t bother me personally, but I’m horrified by the idea of another intelligent species coming to visit and seeing all the crap floating around. They would immediately see that our space capacity is pretty limited (“Whatever animal lives on this planet can get stuff up, but can’t get it down”), and that we’re launching stuff despite our inability to clean it up.

It would be like an old friend from college who’s done really well swinging by your place on a business trip after you’ve just gotten over a cold. The sink is full of dirty dishes, you’ve stopped showering, and there are balled up snotty tissues literally everywhere. Your friend doesn’t say anything, but you can tell that they’re kind of grossed out and they end up not staying very long.

Hopefully we can clean up low Earth orbit before the aliens come to visit.

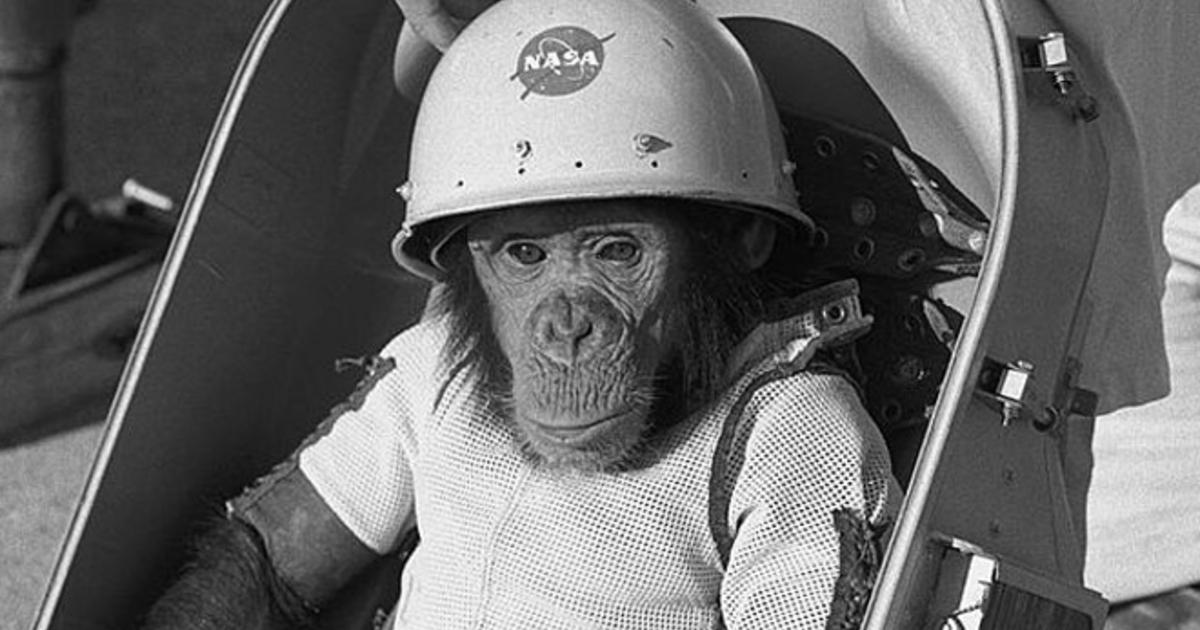

2.) Our closest genetic relatives

In January 1961, Ham the chimpanzee became the first primate to visit space when he was strapped into a Mercury-Redstone 2 rocket and launched from Cape Canaveral into suborbit. His capsule was recovered later that day in the Atlantic Ocean and Ham was declared a hero. His survival also cleared the way for Alan Shepard’s flight later that year. After his death in 1983, Ham’s remains were buried at the International Space Hall of Fame and a memorial service was held honoring his contribution to space exploration.

The pleasant way to think about Ham is to talk about what he did. The weird way is to talk about what was done to him. As a baby, Ham was captured by hunters in Cameroon, sold to an animal farm in Florida, then bought by the Air Force. He was trained to use the equipment aboard the MR-2 by having electric shocks administered to the bottom of his feet when he failed to do a procedure correctly. During his flight, Ham’s capsule lost pressure, and when he landed in the Atlantic, the recovery ship couldn’t find him for several hours. After Ham was recovered, several photographers requested to take pictures of him inside the capsule, but according to Save the Chimps, Ham “refused to go back into it, and multiple adult men were unable to force him to do so.”

He didn’t get the name “Ham” until after the flight, because in the event the mission failed, NASA didn’t want the American public freaking out over a cute little dead chimp with a human-sounding name.

And you know what? We knew it was weird to send Ham into space when we did it. According to Donna Haraway’s Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science , Ham was called Chimp 65 prior to launch. He didn’t get the name “Ham” until after the flight, because in the event the mission failed, NASA didn’t want the American public freaking out over a cute little dead chimp with a human-sounding name.

Speaking of little: Ham was only three-and-a-half-years-old when he went to space. Chimps can live as long as 50 years in the wild, upwards of 60 years in captivity, and their developmental stages mirror those of humans. Which essentially means we electrocuted a toddler’s feet, strapped him on top of an explosive device, sent him into space, then let him sit in the Atlantic ocean for several hours.

But wait, it gets weirder: The Russians also sent animals to space, and after those animals died, the Russians stuffed them and put them in a museum. The U.S. Government thought this was neat and so after Ham died, they decided to stuff him and put him in the Smithsonian. And do you know what happened? People freaked out and said stuffing Ham would be like stuffing a human astronaut. So instead they dissected him for medical research and then buried his remains in New Mexico.

1) Ourselves

Let’s say modern humans first appeared on Earth 50,000 years ago, after several million years of hominid evolution. How many humans have lived on Earth since then? Roughly 108 billion.

In that 50,000 year span, do you know how many humans have gone to space? Less than 600.

They were and are some of the smartest, most accomplished humans alive, and we sent them to a place where they can’t breathe on vehicles that don’t always work. That’s very, very weird.

Consider the first two humans to travel to space. Yuri Gagarin was born to Russian farmers in 1934. During World War II, his siblings were put in Nazi labor camps while he and his parents were forced to live in a tiny mud hut. After the war, he went to school to learn about tractor repair and learned how to fly on the weekends by using a biplane. This is a biplane.

In 1960, he became one of 20 people in a country of 208 million to be selected for the nascent space program. And do you know why the Soviets chose Yuri Gagarin to be the first human to fly into space? Because he was brilliant and emotionally intelligent and perfectly qualified in pretty much every way, down to a height of 5’2. Then the Soviets took this brilliant person and strapped him into what was essentially a giant rickety bomb and pointed it at the sky and fired the thing up, all the while having no freaking idea whether or not he’d survive.

And that inspired the Americans, who had already lost the satellite race, to ready their own perfect person: Alan Shepard skipped two grades and got into the U.S. Naval Academy at 16, but couldn’t go because he was too young. He served in World War II, volunteered to be a test pilot, and then in 1959 became one of seven people in a country of 180 million people tasked with going to space.

The resumes of pretty much every human who’s gone to space since Gagarin and Shepard are as impressive if not moreso. Which basically means that for the last 55 years, we’ve taken some of the smartest, most resilient, level-headed and adaptive people in the world and strapped them to giant bombs. We have literally never sent an unintelligent or even just average person to space, even when we were first doing it and had no idea if anybody would survive.

That’s kind of weird. It’s also kind of great.