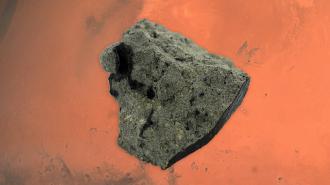

Researchers have carried out the most detailed analysis yet of a Martian meteorite that landed in Morocco in 2011, documenting over 20,000 organic molecules in the sample. The results showcase the diverse and complex geochemistry that has played out both on and beneath Mars’ surface.

Their results offer new insights into the planet’s geological past.

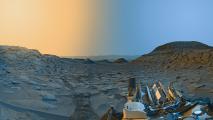

Life on Mars? The possibility of life on our planetary neighbour has captivated us for centuries, and is still one of the most actively-explored branches of planetary astronomy. Many astronomers believe that life may once have thrived on the Martian surface in the distant past, and that microbial remnants of these ancient ecosystems could still be holding on beneath its surface.

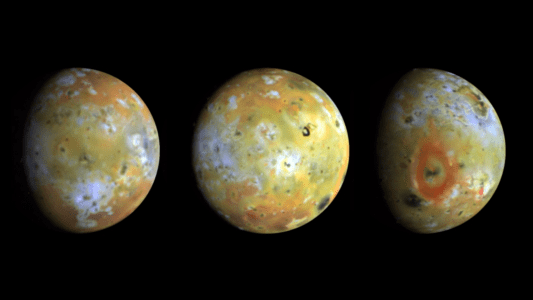

Samples of the Red Planet have come to us in the form of meteorites.

Along with a history of liquid water, evidence supporting this possibility can be found in carbon-based organic molecules, which are widely seen as basic prerequisites for a planet to evolve life (although such molecules can form without life, too). Since Mars shares some similar geological history with Earth, studying these molecules on Mars is not only valuable in the search for extraterrestrial life, they could also offer vital insights into how life first emerged on our own planet.

Organic compounds are now being actively searched for and studied by Mars missions including NASA’s Perseverance Rover and China’s Zhurong mission. While we have yet to bring samples back from Mars, in a few cases, samples of the Red Planet have come to us in the form of meteorites — rocks launched from the Martian surface by violent events, such as asteroid impacts or volcanic eruptions, which eventually found their way across space to Earth.

Unfortunately, Martian meteorites are incredibly rare. So far, just five Martian meteorites have been recorded since 1815, making it all the more important for astronomers to carefully analyse and identify the compounds they contain.

The Tissint meteorite: In 2011, a new opportunity came when a Martian meteorite fell to the Sahara Desert, close to the city of Tissint in Morocco. For a few local residents, the event briefly lit up the night sky with a bright fireball.

Following the impact, researchers were able to recover 17 kg of meteorite fragments from the desert, providing astronomers with a vital source of fresh, largely contaminant-free material. Initial analysis of the Tissint meteorite revealed that it likely crystallised over 650 million years ago, and it contains a diverse array of organic compounds.

They examined the Martian meteorite’s molecular makeup using a variety of cutting-edge approaches.

A molecular atlas: Through a new study published in Science Advances, an international team led by Philippe Schmitt-Kopplin at the Technical University of Munich have examined the Tissint meteorite in the most extensive level of detail to date.

In their study, the team first crushed a small sample of the Tissint meteorite into a fine powder, and dissolved it in a methanol-based solvent. They then examined its molecular makeup using a variety of cutting-edge approaches to mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy, as well as electron and x-ray microscopy.

Through their analysis, Schmitt-Kopplin and his colleagues built up an atlas of over 20,000 organic compounds in the meteorite, many of which have never before been found in Martian rocks. The molecules they found included carboxylic acids, aldehydes, olefins, and polyaromatics – but perhaps their most interesting findings were over 1,000 molecules containing magnesium, which likely formed at extreme temperatures and pressures.

Such conditions could have been triggered by geological processes in Mars’ mantle or crust, or during high-energy asteroid impacts, like the one that may have ejected the rock into space. Either way, the result hints at the close ties which could have formed between the complex organic compounds and magnesium-carrying minerals inside Martian rocks.

The team’s atlas will provide a valuable resource for astronomers as they explore Mars’ geological past.

Fetching samples: The compounds found in the Tissint meteorite don’t necessarily allude to the past presence of life on Mars; organic compounds can and often do form through inorganic, geological processes, as well. But they showcase a remarkable diversity of complex chemical reactions that once took place on our planetary neighbour.

Ultimately, the team’s atlas will provide a valuable resource for astronomers as they explore Mars’ geological past, and the parallels which could be drawn with the evolution of life on Earth. In the future, astronomers won’t have to rely solely on elusive Martian meteorites to study samples. In the coming decade, NASA and ESA plan to launch the Mars Sample Return mission, which will deliver Martian rocks collected by rovers directly back to us on Earth.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.