On a Sunday night in October, 17-year-old Donald McCaney successfully convinces his mom that he needs to meet up with friends. “Mom, I’ll be right back,” he tells her as he heads to the 7/11 where his friends are waiting.

Two hours later his mom, DeVitta Briscoe, is wondering when ‘right back’ will be.

Her cell phone rings—it’s not Donald.

Shortly thereafter, Briscoe finds herself in the car with her ex-husband heading to the hospital. “It was one of the longest, darkest rides of my life. I swear it took about two hours to get there but it was really only 10 minutes,” Briscoe recalls.

That night in southern Tacoma in 2010, Donald’s name was added to a long list of nearly 10,000 people killed by gun violence nationwide that year.

“Witnesses described a scene with multiple fights involving members of two street gangs. They saw (one teen) pull a gun and fire multiple shots,” court documents state. One of those shots inadvertently hit Donald who, according to reports, was being beaten up by rival gang members. The shooter, Datrion Newton, had recently been released from juvenile detention for the unlawful possession of a firearm. He claimed he hadn’t meant to shoot Donald.

“He had only been out for a couple of days and went and got another gun,” says Briscoe. Newton, who was 17 at the time, was charged as an adult and sentenced to 26 years in prison—a sentence that represents the high end of the standard range. Briscoe, however, wasn’t satisfied.

“What would have met my needs was the lower end of the sentencing range, which I think was 12, 13 years. I think that would have been justice for me,” says Briscoe before adding that Newton should not have been tried as an adult. “I was more concerned about his safety and what’s going to happen to him in an adult facility.”

Briscoe never had a chance to request a lighter sentence for her son’s killer because she didn’t attend the sentencing hearing.

She says was never notified of it.

The Tale of the Vengeful Victim

Briscoe is far from the only crime victim who feels left out of the justice process. While it is the harm sustained by a victim that launches a criminal prosecution, the modern criminal justice system is set up to reconcile disputes between the state and the defendant, not between the victim and the defendant. Victims, therefore, can often feel like a pawn of the prosecution—useful sometimes but not valued enough to have their needs and desires taken seriously.

“By taking the initiative away from victims, according to the conventional wisdom, the state curbs the danger of vendettas and blood feuds and sets limits on arbitrary, cruel, and excessive punishments,” writes Judith Herman, professor of clinical psychiatry at Harvard, in her 2005 study Justice from the Victim’s Perspective, “The presumption that the state will be more dispassionate, fair, and less punitive than the victim is rarely questioned.”

However, in 2016 the Alliance for Safety and Justice turned the caricature of the vengeful victim on its head by releasing the first national poll of crime survivors that examined their criminal justice policy preferences. The study found that 61 percent of crime victims polled support shorter prison sentences and more spending on prevention and rehabilitation over long prison sentences. They also prefer more investments in education, mental health treatment, drug treatment, and job training than more spending on prisons and jails.

“It is crucial to note that survivors’ opposition to incarceration is strongest when other options are present,” wrote Danielle Sered in her 2017 Accounting for Violence report for the Vera Institute of Justice. “When prison is the only option available to survivors, many will choose it—if only because choosing “nothing” is unacceptable to them.” Sered is a leader in the growing restorative justice movement in the US and through her non-profit Common Justice, she’s on a mission to give victims a third option.

Challenging State-Monopolized Justice

Had she been given the choice, Briscoe would have chosen a restorative justice path rather than going through the traditional criminal justice process. Restorative justice brings together those that have been harmed by the crime and those that did the harm in an effort to heal both sides and hold the offending side accountable. It’s actually not a new practice as many of the principles and values can be traced back to indigenous cultures. But as reformers look for alternative solutions to the broken status quo, restorative justice programs are increasingly in vogue. At least 35 states in the US have legislation that promotes the use of restorative justice both before and after prison and these programs are expected to increase in popularity over the next decade.

Through victim-offender dialogue, restorative justice gives victims the opportunity to share with the offender and other community members the impact the crime has had on their life, to have their pain recognized and their questions answered, and to feel in control over the outcome of the crime. The offender must, in turn, acknowledge the harm caused and take the agreed upon action to repair the damage as best as possible.

By combining accountability with rehabilitation, restorative justice challenges the idea that state punishment is the best method of achieving justice.

Victim-offender reconciliation dialogue can happen at any point in the aftermath of the crime: on an informal community-level without notifying authorities; in diversion programs before sentencing occurs; or after sentencing, usually in the prison setting. Among other principles, Sered emphasizes the need for any restorative justice program to be both survivor-centered and accountability-based.

“A survivor-centered system is not a survivor-ruled system,” writes Sered, “so if a survivor wants someone free and that person poses a present and demonstrable threat to others, the survivor’s opinion should not outweigh the safety of others. Similarly, when a survivor wants a level of retribution that runs contrary to the values of justice and fairness, the system does not have an obligation to satisfy the person’s desire for punishment. The system’s actors do, however, have an obligation to listen to the survivor, be transparent and honest with the person about the decisions they make, and connect the survivor with support.”

Most restorative justice programs in the US handle non-violent crimes committed by juveniles and are not typically diversion-focused; meaning, the outcome of restorative meetings has no impact on the punitive sentencing handed down by the state. Sered’s program, Common Justice, is among the few diversion programs in the country that specifically deals with violent crimes committed by adults. In diversion programs, the case gets moved out of the traditional process and the retribution that is agreed upon in the restorative meetings is taken into consideration when it comes time for sentencing.

Successful restorative justice programs must also be accountability-based. “Some survivors certainly do want punishment. But what nearly all survivors want is real accountability on the part of the people who hurt them. And punishment and accountability are not the same thing. Punishment is passive—it means someone else doing something to you. Accountability is different,” writes Sered, “It requires five key elements: acknowledging one’s responsibility for one’s actions, acknowledging the impact of one’s actions on others, expressing genuine remorse, taking actions to repair the harm to the degree possible, and no longer committing similar harm. Unlike punishment, accountability is not passive. Far from it. It is active, rigorous, and demands the full humanity of people who have committed harm.”

Ninety-percent of crime survivors in New York City, where Common Justice is based, choose restorative justice when the option is offered and benefit from the assistance of Sered and her team. Only seven percent of these program participants have been terminated for committing a new crime. Meanwhile, the national recidivism rate for state prisoners hovers around 44 percent, according to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report published in 2018.

The Greater the Hurt, the More Powerful the Restoration

“If we’re going to address some of these major issues like mass incarceration we have to address violent crimes,” Briscoe says. She’s right. Fifty-three percent of those in state prisons—where the vast majority of inmates are held—are locked up for violent crimes. If this approach is going to make a big impact, it has to be able to help with violent offenders. “I think it’s equally important (to implement restorative justice) across the board including sexual assault, murder, assault, robbery. I know that not a lot of people are doing it, but I believe that it could be, and I believe that it should be.”

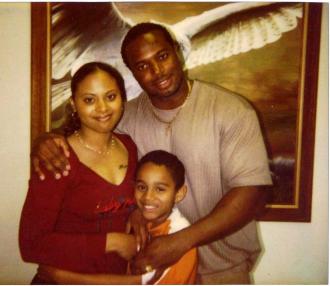

Briscoe, a cheerful, straight-forward, self-described Christian does more than talk about this importance. Along with her co-founder Martina Kartman, she’s implemented a restorative justice program called the Community Justice Project in Seattle, Washington; a program she wishes she had available to her in the aftermath of her son’s death. The program operates in partnership with the Public Defender Association, API Chaya and the University of Washington Center for Human Rights.

“I would have wanted some intervention in his life because he has a release date. At some point he’s going to reenter the community again,” says Briscoe of her son’s shooter,

“And who’s to say that sitting in prison for 20 years that he’s rehabilitated? That he’s started any process towards rehabilitation or deep accountability and healing?”

To help others start that process, Briscoe and Kartman have devised a three-pronged restorative justice process. First, they have a 15-month accountability program that involves working with inmates who have already been convicted and sentenced for their violent crime. It’s a long-term, rigorous approach designed to develop introspective skills that help offenders understand why they’ve caused the harm they did and how they can meaningfully be held accountable.

Then, Briscoe and Kartman mirror that curriculum for the victims but with more of a focus on trauma healing. At the end of their curriculum, victims have an opportunity to go into prison and share their stories with the class of offenders. It’s not a direct victim-offender dialogue; the offender and victim aren’t necessarily related by the same crime. However, these victims and offenders have all been touched by the same type of crime—sexual assault, robbery, gun violence—and sharing their perspectives can help in the healing process.

“A story is told and someone else is like, ‘That’s the same thing I did,’” Kartman says, “We just had about 12 or 13 people go through a restorative justice-based process, who have survived violence, and then they came into the prison and shared their stories, and for that group about half are parents who’ve lost their children to gun violence.”

Kartman says she’s seen profound shifts in the way people talk about what happened and their own accountability. “We had someone in our circle who was really resistant at first. He said something to the effect of ‘I don’t feel bad that I killed this person.’ He had a lot of anger in his voice and there were elders in our circle that looked really upset,” recalls Kartman. She was able to calm the group and ask the young man why he felt that way. That simple question elicited tears: the person he killed had caused the death of someone he loved. The young man had lost his father, cousin, and best friend to violence at a young age.

“He started crying. There was a profound shift in him,” says Kartman. The young man came back to the restorative justice circle the next week and said he never meant what he said about not caring.

Kartman says,

“It’s really difficult to ask a person who has experienced harm their whole life to be empathetic toward someone they harmed when they’ve never been witnessed in their own healing.”

That healing can have a profound impact not just on an individual level but for the whole community.

“(Restorative justice) is not as powerful, frankly, when it’s like ‘I stole a candy bar’,” argues Kartman, “when serious harm has happened between individuals, when repair is really needed in a relationship or in a community, (restorative justice) will have a powerful impact.”

Briscoe emphasizes that harm can have ripple effects that aren’t always obvious.

“A lot of times the people who are committing the harm are from the same communities where the harm happens. I didn’t know (my son’s shooter) or his family but eventually I ran into the nail salon and sat right next to his aunt, and we were getting pedicures. Then his grandmother came to the association where I was working to give a rental voucher. I was her housing specialist to help her get rent assistance. I run into his family all the time. That’s why I would have been open to that type of dialogue—there’s this brokenness between these two families. How do we as a community repair that harm and then how do we bring peace back and rebuild those relationships that have been broken?” says Briscoe.

Envisioning What Doesn’t Exist: Building a New Sentencing Process

The Community Justice Project run by Briscoe and Kartman is seeing promising results in the individual lives of the people who attend the classes. Even so, they are well aware that to really impact the criminal justice process more work needs to be done on the front end to keep people from receiving long prison sentences—or keep them out of prison altogether. They are currently working with Dan Satterberg, the King County Prosecuting Attorney in Seattle, Washington to create a diversion program similar to Sered’s Common Justice.

“I have every reason to think that it would work as well here as it does in Brooklyn,” says Satterberg, “The reason that we don’t have it (in King County) and that a lot of other people don’t have it is that it’s really complicated.”

The complications largely have to do with scale.

“You can’t just open shop and all of a sudden do hundreds and hundreds of cases at a time. It actually takes a lot more time to go through a proper restorative process then it is just to jam one more case into the (traditional) system,” Satterberg says, “You wouldn’t do it as some sort of efficiency. It’s kind of the opposite of efficient.”

“The courtroom is efficient, but it isn’t very impactful.”

Satterberg spearheaded a juvenile diversion program last year for youths charged with nonviolent felonies. While the community is very supportive of these programs, he received pushback when the restorative program was not available to everyone on an equal basis. Satterberg says this was due to capacity issues: programs like this need money and community engagement.

“We started doing these individual experiments. The pushback I got was, “Well, let’s make this available for (every juvenile offender).” So that’s kind of been our focus the last couple years, is to come up with a menu of community group partners that we can fund to take the cases out of Juvenile Court and to make (restorative justice more) available. That is important to me to get that kind of scale up.”

Briscoe still wants to do a restorative justice process with her son’s shooter. She put in the paperwork over four months ago but has not been notified of anything yet.

“I want to know what were my son’s last words as he was holding him.”

“I also want to know who called this meeting that he was on his way to. I still don’t know why he felt he had to be there and what this meeting was all about.”

Over eight years later, Briscoe’s lively voice wanes as she says, “I still don’t know.”

Satterberg is eager to give victims like Briscoe and offenders like Datrion Newton a chance to find closure and healing.

“I’m always frustrated with the pace of change because it just takes a long time to build something that isn’t there now,” says Satterberg, “we have to have somebody out there who’s envisioning what doesn’t exist now.”