There is little point in attempting to deny the general deliciousness and culinary import of sugar. It is more than cheap energy and sweet flavor; it thickens spreads, carmelizes for browning, and can be used to preserve foods or produce acidic environments hostile to pathogens.

It is also, when highly processed and consumed in large amounts, linked to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic health conditions. And the sugar isn’t only in places you’d expect, like pop and candy — it’s also hiding out in bread, soups, cured meats, and myriad other foodstuffs.

Sugar is important beyond just being sweet — but it’s also linked to health problems, especially when highly processed and consumed in large amounts.

“Myriad other foodstuffs” is an apt description for what the Kraft Heinz Company produces, and in a drive to reduce the amount of total sugar in their products by 60 million pounds come 2025, they have turned to Harvard’s Wyss Institute.

“We thought we’d come to the Wyss with an impossible problem, and they turned it on its head to present an even crazier idea to solve it,” Judith Moca, Kraft Heinz head of technology discovery and development, said.

That impossible problem lay in sugar’s various properties beyond a sweet flavor. Creating a substitute that could achieve all or most of these other functions could prove difficult. The Wyss team’s proposal: why not change sugar itself?

Researchers in the labs of Wyss founding director Don Ingber, Jim Collins, and Davie Weitz landed on using enzymes inspired by the kind that plants use to turn sugar into fiber.

Creating a substitute that Kraft Heinz could replace sugar with may have proven difficult. The Wyss team’s proposal: why not change sugar itself?

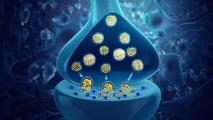

The team was able to create an enzyme that would remain encapsulated until it hit an increase in pH — like when it moves from the stomach to the intestines. Thus freed, it converts the sugar into fiber, leading to less sugar being absorbed by the body.

Crucially, the encapsulation means the enzymes can be used in already-existing food manufacturing processes and recipes.

“Beyond just finding a solution that was technically sound, it was equally important to us that our solution would actually work in the real world of food manufacturing, because something that only works in lab conditions isn’t very useful,” Wyss senior engineer Adama Sesay said.

Researchers landed on using enzymes inspired by the kind that plants use to turn sugar into fiber, potentially making it healthier.

The enzyme is currently being tested in mice to understand how it impacts dietary sugar in a living organism — one imagines, perhaps, via tiny little mouse-sized cookies? — and eventually hope to offer the product for sale to food companies.

“Projects like this are a large reason why the Wyss Institute was created: to take on real-world problems that are too thorny for companies to solve on their own, and create novel solutions that can have immediate, positive impact,” Ingber said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.