For nearly two centuries, scientists have known that humans descended from the great apes. But it’s proven difficult to precisely map out the branches of that evolutionary tree, especially in terms of determining when and where early Homo species first developed brains similar to modern humans.

There are clear differences between ape and human brains. Compared to apes, the Homo sapiens brain is larger, and its frontal lobe is organized such that we can engage in toolmaking, planning, and language. Other Homo species also enjoyed some of these cognitive innovations, from the Neanderthals to Homo floresiensis, the hobbit-like people who once inhabited Indonesia.

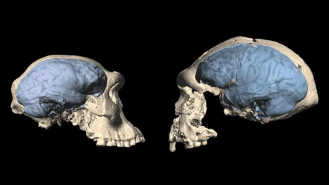

One reason it’s been difficult to discern the details of this cognitive evolution from apes to Homo species is that brains don’t fossilize, so scientists can’t directly study early primate brains. But primate skulls offer clues.

Brains of yore

In a new study published in Science, an international team of researchers analyzed impressions left on the skulls of Homo species to better understand the evolution of primate brains. Using computer tomography on fossil skulls, the team generated images of what the brain structures of early Homo species probably looked like, and then compared those structures to the brains of great apes and modern humans.

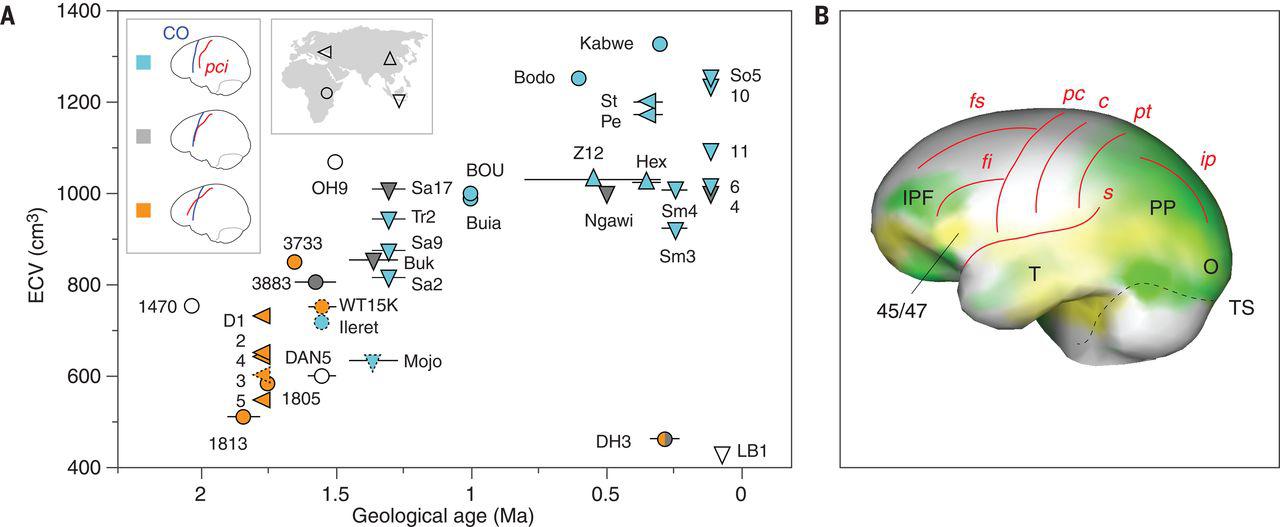

The results suggest that Homo species first developed humanlike brains approximately 1.7 to 1.5 million years ago in Africa. This cognitive evolution occurred at roughly the same time Homo species’ technology and culture were becoming more complex, with these species developing more sophisticated stone tools and animal food resources.

The team hypothesized that “this pattern reflects interdependent processes of brain-culture coevolution, where cultural innovation triggered changes in cortical interconnectivity and ultimately in external frontal lobe topography.”

The team also found that these structural changes occurred after Homo species migrated out of Africa for regions like modern-day Georgia and Southeast Asia, which is where the fossils in the study were discovered. In other words, Homo species still had ape-like brains when some groups first left Africa.

While the study sheds new light on the evolution of primate brains, the team said there’s still much to learn about the history of early Homo species, particularly in terms of explaining the morphological diversity of Homo fossils discovered in Africa.

“Deciphering evolutionary process in early Homo remains a challenge that will be met only through the recovery of expanded fossil samples from well-controlled chronological contexts,” the researchers wrote.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.