Yale University researchers have discovered a DNA-damaging molecule in the gut that could be driving colorectal cancer — and it may give us a way to prevent the deadly disease.

The disease: Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer globally and the second most deadly. It’s also one of the more preventable cancer deaths — colonoscopies can allow doctors to spot and treat the disease before a patient even begins to experience symptoms.

Everyone over the age of 50 should undergo regular colonoscopies, but many people don’t — common reasons people give for skipping the less-than-pleasant procedure include a belief that, if they don’t have symptoms or a family history of colorectal cancer, they don’t need it.

Now, there may be a way to use our guts to not only get more people screened for colorectal cancer, but also prevent the disease.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer globally and the second most deadly.

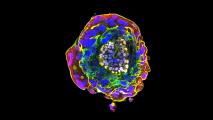

The study: Our guts are home to 300 to 500 species of bacteria. Most of them are helpful to our bodies, but some can produce DNA-damaging molecules, known as genotoxins, and past research has linked one genotoxin — colibactin — to colorectal cancer.

For a new study, Yale scientists analyzed bacteria from the guts of people with inflammatory bowel disease — a known risk factor for colorectal cancer — and discovered a new family of genotoxins called “indolimines” that are produced by the bacteria Morganella morganii.

In mouse models, the presence of M. morganii in the gut exacerbated the rodents’ colorectal cancer. But if the bacteria was altered so that it couldn’t produce genotoxins, the effect was eliminated.

Looking ahead: Scientists are only just starting to explore the link between genotoxins and colorectal cancer, and there is still a lot they don’t know, including whether the effect seen in mice translates to people.

Future treatments might be able to prevent colorectal cancer by reducing or eliminating genotoxin-producing gut bacteria.

Based on their study, the Yale team believes M. morganii may be just one of many gut microbes capable of damaging our DNA, and we don’t know exactly how its impact on colorectal cancer might compare to others we’ve yet to discover.

Eventually, though, the discovery of indolimines could lead to novel treatments designed to reduce or eliminate M. Morganii and other genotoxin-producing bacteria in the gut to prevent cancer.

It could also spur the development of new fecal tests that screen samples for bacteria linked to colorectal cancer — if this simple test uncovers the presence of the bacteria, it might be enough to encourage people to finally schedule that colonoscopy.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.