Long sought out by white guys in ill-fitting earth toned striped hoodies or people going camping, magic mushrooms are now at the center of a research revolution.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research (CPCR), which opened this past September, has been at the forefront of psychedelic mushroom research, pushing to move the drug out of Schedule I (drugs declared to have no medical value) by demonstrating its possible uses for treating addiction and depression, among other afflictions.

Come along for the ride as the Dope Science Drug Guide expands your mind, duuuuuuuudeeeeeee…

What’s this “magic mushrooms” drug now?

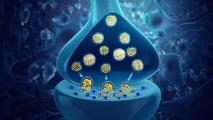

Outside of the kitchen or grocery store, when someone asks you for shrooms, they likely mean psilocybin mushrooms. These types of psychedelic mushrooms produce, duh, psilocybin, a naturally produced psychoactive compound.

Why do people get high on this stuff?

According to PubChem, people have been using psychedelic mushrooms for spiritual experiences since before the Spanish ran roughshod over the New World. In addition to psilocybin mushrooms’ potential to create spiritually meaningful experiences — which Hopkins wants to research, by the way, for all the priests and spiritual leaders reading — people just flat out enjoy the psychedelic effects they cause.

You may know the ones I’m talking about: objects and walls “breathing,” patterns moving, hearing (and maybe seeing!) music like you never have before.

What’s the new medical research?

Roland Griffiths, director of the CPCR, has been studying the effects of psychedelic mushrooms since 1999, including their impact on anxiety and cigarette addiction, as he told Anderson Cooper on 60 Minutes in October.

A 2016 clinical trial at NYU suggests psychedelic mushrooms may help alleviate depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer, findings backed up by reports from Hopkins and UCLA as well.

“It’s remarkable,” says Matthew Johson, associate director of the CPCR. “I mean, huge reductions. Statistically, these were larger than large effect sizes … most people getting down to the ‘clinically not diagnosable range.'”

While in a much more preliminary state, data from Imperial College London shows the same potential in people with treatment-resistant depression.

There’s also been a growing grassroots trend of micro-dosing psilocybin for depression, anxiety, or just all-around better living, but the science isn’t there yet, Johnson says. His anecdotal evidence runs the gamut from feeling energized to not really noticing much, so the jury’s out.

The scientific studies all used trip-inducing doses of psychedelic mushrooms.

“The so-called ‘mystical experience,’ that’s predictive of long-term success,” Johnson says.

Psychedelic experiences may be key to psilocybin mushroom’s medicinal effects.

In 2017, researchers at Karlstad University in Sweden found that low doses of mushrooms have potential in preventing and treating excruciatingly painful cluster headaches. It’s still in the preliminary stage, but people’s stories are promising.

Next on the docket is research into psilocybin’s potential effects on anorexia and mild cognitive impairment/Alzheimer’s disease at, you guessed it, Johns Hopkins (lacrosse and shrooms: it’s what Blue Jays do). The idea is to see if psilocybin’s ability to reduce depression and anxiety and lead to positive life changes will work with these patients.

The promise and the pitfalls.

Griffiths and Johnson report little opposition to their psilocybin research, as long as they are doing it safely, and a quick perusal of Google seems to back that up. The data looks strong, especially for treatment of depression and anxiety. There are still special challenges researchers face when it comes to mushrooms, however.

One of the most difficult is placebo blinding: it’s kind of obvious if you’re tripping or not. Researchers deploy a number of methods to help get around psychedelic mushroom’s noticeable impact on patients in the placebo arm of the study.

“In one study, we used a really high dose of ritalin with people who had never taken a psychedelic before,” Johnson says, “and this did fool a number of people.”

Rather than controlling for the substance, they can also control for the dosage. Participants could be told they may receive a low, medium, or high dose of psilocybin, without knowing which they have received.

With high doses come psychedelic experiences, and those experiences may in fact be key to psilocybin mushroom’s medicinal effects. But bad trips are no joke — your correspondent knows this from experience — and researchers must ensure safety for this unique aspect of their study. (In Hopkins’ parlance, they are “challenging experiences,” a euphemism meant to evoke their potential for opportunity, as well.)

To prevent lasting damage, participants must be screened for a potential psychotic disorder, like schizophrenia, which can be exacerbated by psychedelic trips. Specially trained session facilitators help guide people through their trips, which is considered best practice, Johnson says.

Whether in the lab or the “bad trip” tent at Burning Man — he’s done it — just having someone to talk to can make all the difference. After their experience, subjects also talk through their trip.

While there are drugs which can arrest a trip — think shroom Narcan — and benzodiazepines (like Xanax) that can make things easier, they are rarely needed in Johnson’s experience.

“There are definitely risks, but there are also definitely ways to address them and mitigate those risks,” Johnson says.