Chronic pain is a huge problem in the US. One in five adults has been in pain most days for at least three months — the minimum criteria for chronic pain — and for many, pain has been a part of daily life for years.

Chronic pain can make it hard for a person to work, socialize, or even do tasks around the house, like cooking or cleaning. It can also affect sleep and lead to mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety.

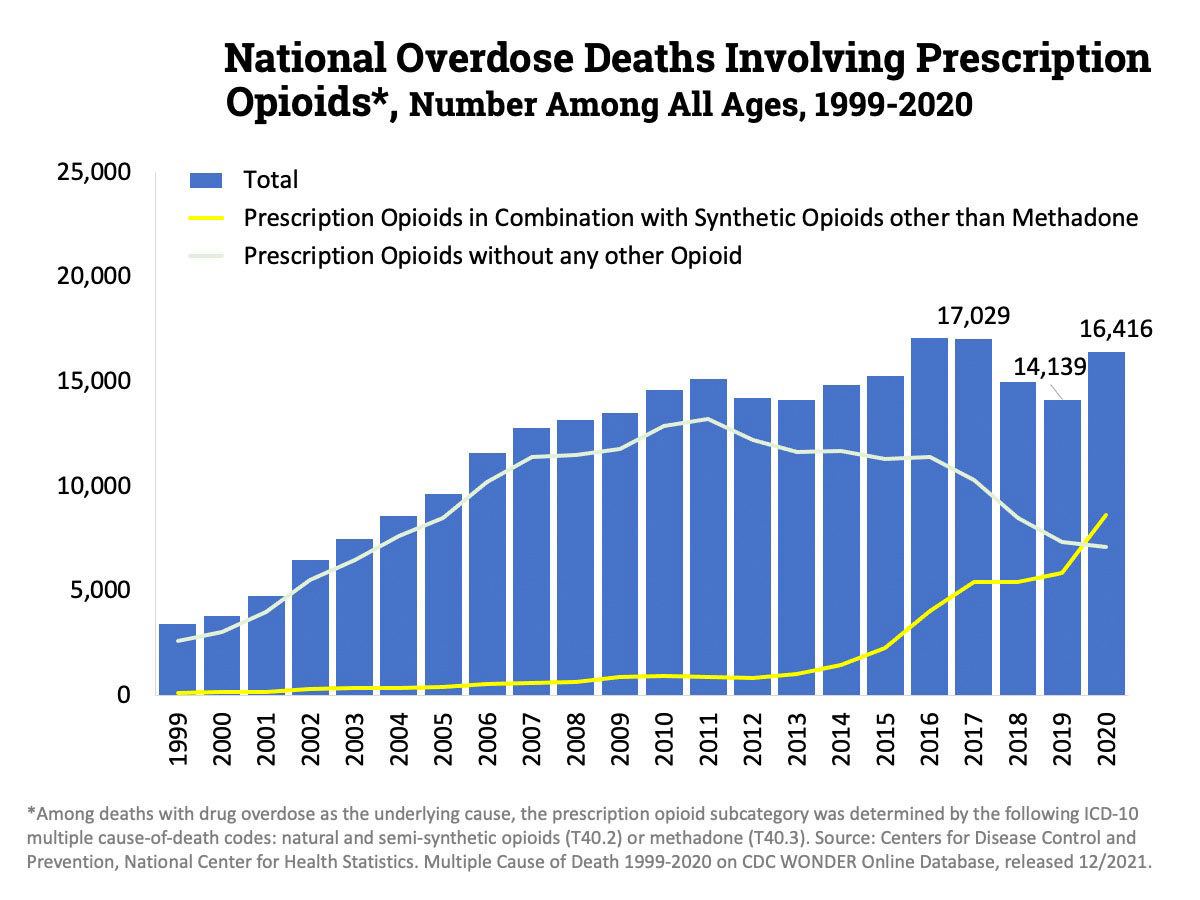

Opioids, such as oxycodone and morphine, are commonly prescribed to treat both chronic and severe acute pain, but while they’re effective, they’re also addictive and widely misused — 16,000 Americans now die every year from in overdoses involving prescription opioids (though an increasing share also involve fentanyl).

Even when used properly, opioids have a variety of side effects that makes them a less-than-perfect solution to pain. As a result, we’re in dire need of more effective, safe alternatives to opioids.

Here are a few promising candidates from the cutting edge.

Gene Therapy

How it works: Gene therapies treat or prevent health issues by targeting the genes linked to them. This includes replacing faulty genes with working copies and inserting new genes to interfere with ones causing problems.

Where we are now: One promising gene therapy for chronic pain relief targets the protein NaV1.7. People with mutations that prevent production of this protein don’t feel pain at all, while those with mutations that increase its production are hypersensitive to pain.

Armed with that knowledge, researchers at UC San Diego developed a therapy that treats pain by temporarily reducing production of the protein.

Gene therapies treat or prevent health issues by targeting the genes linked to them.

In March 2021, they announced that mice treated with the therapy had higher pain thresholds than untreated mice. The effect lasted for months, and the animals exhibited no obvious side effects.

The gene therapy still needs to prove itself in humans — and many treatments don’t make the jump — but the researchers believe it could help people with a number of conditions that cause chronic pain, including sciatica and osteoarthritis.

The drawbacks: Gene therapy is still experimental, and there’s always the potential that the treatment will cause unexpected side effects. However, because the treatment only temporarily dampens the gene, rather than permanently altering it, it is likely simpler and less risky than gene therapy that alters DNA.

Sodium channel modulators

How they work: NaV1.7 belongs to a group of proteins (known as “voltage-gated sodium channels”) that are involved with processing pain.

Instead of working on the genes themselves, some researchers are developing non-opioid medications (called “sodium channel modulators”) to relieve pain by interfering with these proteins.

Where we are now: Vertex Pharmaceuticals recently announced the promising results of phase 2 trials testing its drug, VX-548, as a treatment for acute pain following surgery.

During the trials, patients were given either the new medication, a placebo, or the opioid hydrocodone. A high dose of the new drug outperformed the placebo at reducing pain and saw no serious side effects.

Patients who received the high dose of VX-548 reported more benefits than those who took hydrocodone, but the trials were too small to confirm that it actually works better. Larger trials will be needed to compare the two types of meds, as well as assess VX-548’s ability to treat chronic pain.

Medications that interfere with proteins called “voltage-gated sodium channels” may be able to provide chronic pain relief.

The drawbacks: Several of these drugs have made it to the clinical trial stage and failed. A key problem is that the meds have to be very specifically designed to target one of three sodium channels linked to pain (NaV1.7, NaV1.8, and NaV1.9) and not any of the others — if you inhibit NaV1.4 by accident, you can cause partial paralysis.

This affects the drugs’ ability to make the leap from animals to humans, because these channels are not all identical in mice and humans.

“When you home in very specifically on differences between sodium channels [in one animal], you end up with molecules that are so specific they’re not very good at inhibiting the channel [in a different animal,” William Catterall, a University of Washington pharmacologist, told the Scientist.

Psychedelics

How they work: Studies in the 1960s and ‘70s suggested that psychedelic drugs, such as LSD and psilocybin, could help alleviate chronic pain. Exactly how isn’t fully understood, but it’s thought the drugs induce neuroplasticity in the brain, allowing it to rewire itself in beneficial ways.

Where we are now: The classification of many psychedelics as Schedule 1 drugs — with “high potential for abuse” and “no accepted medical use” — dramatically slowed research into them, but it’s now starting to pick up again.

In 2020, Dutch researchers published the results of a small trial that found that microdosing LSD — that is, regularly taking an amount too small to induce a “trip” — increased participants’ pain tolerance.

Psychedelics are believed to induce neuroplasticity in the brain, letting it rewire itself in beneficial ways.

Several other trials are ongoing. One out of UC San Diego is testing the ability of psilocybin — the psychedelic compound in magic mushrooms — to alleviate phantom limb pain. Another in Switzerland will see if LSD can help alleviate the pain of chronic cluster headaches.

“There are numerous mechanisms in psychedelic drugs, particularly psilocybin, but possibly others, that could potentially affect chronic pain disorders,” Amanda Pustilnik, a neuroscience law expert from the University of Maryland, told VICE. “Their potential could be tremendous.”

The drawbacks: There is still a lot we don’t know about how psychedelics work — or don’t — and their potential drawbacks. That means a lot more research is needed, but because of how these drugs are classified, getting studies approved is difficult. Getting a treatment approved is even harder.

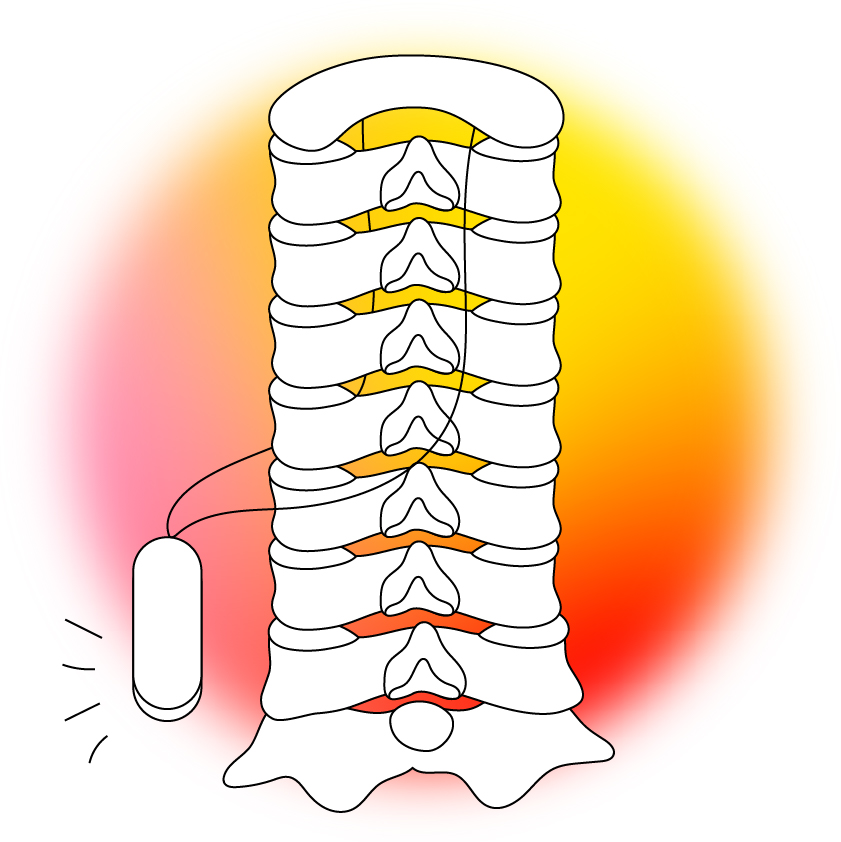

Implants

How they work: Implants can relieve pain by interfering with the electrical signals that tell our brains something hurts.

Where we are now: Doctors have been using implants to manipulate electrical signals in the body and alleviate pain for decades, but the technologies are now getting far more advanced.

Cambridge University researchers are developing an implant that stimulates the spinal cord to alleviate back pain. It’s so small that it can be placed using a needle, so if future clinical trials go well, the tiny device could help people overcome pain without surgery.

At NYU, a team has demonstrated in rats what it says is the first computerized brain implant to target chronic pain. That device works by delivering pain-relieving stimulation to one part of the brain when patterns linked to pain are detected in another.

Implants can relieve pain by interfering with the electrical signals that tell our brains something hurts.

The drawbacks: Even if they work, implants degrade over time, so these devices wouldn’t be able to cure chronic pain permanently — after so many years, they’d probably need to be removed and replaced.

Implanting a device into the body is risky, too, especially if the implant is being placed near the spinal cord or brain. That means this form of pain relief is likely to be reserved only for the most serious cases of chronic pain for the foreseeable future.

Today’s solutions

While waiting for these therapies to clear trials, people experiencing chronic pain do have treatment options other than opioids.

Research suggests that some chronic pain sufferers can benefit from marijuana, even in microdoses too small to produce the drug’s characteristic “high.” Though the research isn’t yet conclusive, the non-psychoactive marijuana compound CBD may also provide pain relief.

Virtual reality and green light therapy have also been shown to help alleviate chronic pain, as has a psychological treatment called “pain reprocessing therapy,” which teaches patients how to rewire their brains — without the use of drugs or surgical implants.

Still, people experiencing severe chronic pain may find that opioids are the only thing that helps, so ensuring that the drugs are prescribed only to those who need them — and that those people have help avoiding or overcoming addiction — is a key part of combating America’s massive chronic pain problem.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.