A team of researchers from UC Davis and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai has demonstrated a new way the influenza virus could possibly be transmitted.

The paper, published in Nature Communications, found that incredibly small particulates in the air — dubbed “aerosolized fomites” — could carry particles of influenza virus from one guinea pig to another, leading to infection.

Aerosolized fomites may now be considered as a new route of transmission, not just for influenza virus but other respiratory pathogens as well — including SARS-CoV-2.

How You Catch the Flu

There’s a general consensus that flu is most often spread via respiratory droplets or by contact with surfaces contaminated with live influenza virus (called “fomite transmission”), but there’s more we don’t know about flu’s transmission routes than you might think.

“It’s something that’s really difficult to study, mostly because humans live in very uncontrolled environments,” says Nicole M. Bouvier, an associate professor of infectious disease and microbiology at Icahn and an author on the paper.

There is plenty of empirical and epidemiological data suggesting certain pathways of transmission, Bouvier says — but they don’t always agree.

The idea of a third route by which the influenza virus may spread — sort of a combination of the two commonly accepted vectors — has been sparsely explored, Bouvier says.

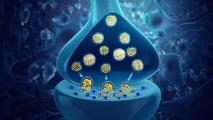

Hewn to the bone, the concept is simple: influenza virus may be hitching a ride not only via the respiratory droplets you are by now undoubtedly familiar with, but tiny particulates in the air — which are not produced by breath.

To put the theory to the test, the researchers turned to a most adorable model: the guinea pig.

Aerosolized Fomites

“We had been doing a lot of measuring of the particles that were coming out of the cage, and there was just so many more particles than could possibly have come from the respiratory tract,” Bouvier says.

Besides breathing the virus out, guinea pigs also smear saliva around their cages, like a kid with crayons. What if particles of dust, dandruff, or something else got contaminated with influenza virus — and then got into the air?

They were able to sample the particulates from the air and culture virus from them — live influenza virus, capable of infecting cells in vitro.

A cuy catching flu provided further evidence.

One of the guinea pigs was purposely infected with flu and allowed to recover. Now immune to the strain, known as Pan99, its body would not be cranking out copies to be expelled via their respiratory system.

The healthy, immune guinea pig’s body was then painted with the influenza virus.

And it infected another guinea pig through the air.

The researchers believe that tiny particles, known as aerosols, were thrown aloft by the first guinea pig’s movements, which carried viruses through air to be inhaled by the second guinea pig.

It’s an important proof-of-concept in a field with so little evidence, which suggests we should be investigating these “aerosolized fomites” and their possible role in transmission.

“We’re not saying everyone’s barking up the wrong tree by focusing on respiratory particles,” Bill Ristenpart, a member of the research team and chemical engineer at UC Davis, told WIRED. “We’re saying there’s a whole other tree that needs to be investigated.”

That includes such basic knowledge as what aerosolized particles exactly are the most likely to be ferrying influenza virus.

“We actually don’t know,” Bouvier says. It would require some “pretty sophisticated” aerosol studies to be able to suss out the plethora of particulates and then determine the culprit. It could be dust; it could be dandruff; it could be hair.

Similarly, we simply don’t know how common a route of infection this is. The researchers and our painted guinea pig friend have shown it is definitely possible; it’s just not possible to know right now how often it happens, or if it happens in, say, ferrets (the gold-standard respiratory model for humans) or people.

“We do not know how important this route of transmission is compared to aerosols that are directly emitted (from the respiratory tract),” Virginia Tech airborne virus researcher Linsey Marr emailed WIRED.

New Route, New Problems

If aerosolized fomites are a viable route for an influenza virus to take, many of our current intervention methods — masks, distancing, air filtration and circulation — should help stop them as it does respiratory droplets.

Still, the proof-of-concept raises questions we should seek answers to. For example, how does humidity, a factor in airborne transmission (like my hair, flying viruses thrive in low humidity), impact tiny fomites as opposed to respiratory droplets? Do we need to reconsider how we use and dispose of tissues?

There’s still so much we don’t know, even about a common, ancient, and slippery foe like influenza virus.

The researchers also found influenza virus on aerosolized fomites created by rubbing a tissue together, although, Bouvier admits, the real-world reason for rubbing snot around for minutes is likely lacking.

More cogently, how careful should we be when, say, changing an infected person’s bed sheets … or removing PPE?

“One of the things I see people do when they take gowns off is they pull it off, then sort of twirl it around to wrap it into a ball to make it easier to put in the trash can,” Bouvier says.

“Maybe you shouldn’t do that.”

Most importantly of all, it demonstrates how there’s still so much we don’t know, even about a common, ancient, and slippery foe like influenza virus.

“We have paradigms that we buy into,” Bouvier says; everybody does it, scientists studying respiratory viruses included.

“It’s not until you start seeing data to the contrary that you start reevaluating your paradigm.”