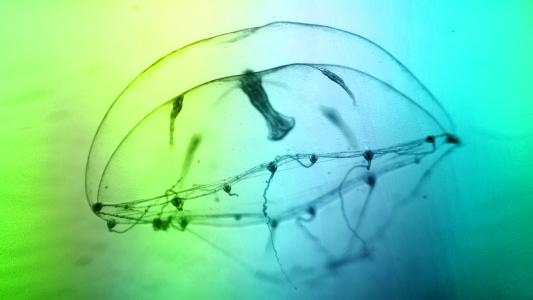

The mosquitofish — a tiny, dart-shaped invader, the color of watered down cappacinos — is terrorizing Australia’s freshwater fish and amphibians.

According to Cell, the invasive fish has got a nasty habit of chewing off the tails of Aussie fish and tadpoles, leaving them immobile while it feasts on the eggs of other fish and amphibians.

In an effort to fight back against the invasive species, researchers at the University of Western Australia, Italy’s University of Padova, and NYU introduced the tail-chewers to what they hope will be their new archenemy: a robotic doppelganger of their natural predator.

“Our robotfish was designed to copy the largemouth bass,” UWA postdoc fellow and lead author Giovanni Polverino said.

The researchers found that the presence of this robo-bass changed the mosquitofish’s behavior, potentially pointing the way to robotic predators guarding waterways against invasive fish and other species.

“It gives us some optimism for the future of freshwater ecosystems, which host more than a quarter of the world’s vertebrates, most [of] which are at the risk of perishing because of the spread of invasive species,” Polverino said.

The invasive mosquitofish is terrorizing Australia’s freshwater fish and amphibians.

One mean invasive fish: Polverino says that the mosquitofish, native to the Southern U.S., is one of the most damaging invasive species in the world, pushing animals to the brink not only in Australia, but also other places they’ve been introduced.

As the New York Times reported, the mosquitofish owes its success to being pretty lax about its living standards. They’ll hang out in “filthy” water, eating not just eggs but also larvae — including those of mosquitoes.

“They thrive, because they eat pretty much everything that moves, and there’s more than enough to be eaten,” Italian biologist Francesco Santi, who did not work on the study, told the Times.

The fish were introduced around the world as a mosquito control measure, but freed from their natural predator, the juvenile largemouth bass, they’ve turned their voracious appetites on local aquatic life with impunity.

In their sights (and bites) are two of the most endangered animals in the antipodes, the Times reported: the red-finned blue eye and the Edgbaston goby.

Polverino and his colleagues had originally created the robotic largemouth bass in 2019, and found that it did, indeed, seem to spook the mosquitofish, whose fear of the bass seems to go wherever the invasive fish do. (Evolution will do that to ya.)

Their new study dug deeper into the impact of their robotic predator on the invasive fish, and it revealed what may be a new weapon: fear.

Introduced to control mosquitos, without their natural predators the invasive fish run roughshod.

Ecology of fear: The study, published in iScience, calls it the “ecology of fear,” possibly my new favorite science term. The robotic bass didn’t just spook the mosquitofish when it was in their tank; it actually impacted their behaviors, breeding, and bodies — even if the invasive fish weren’t actively facing it down.

“It was not only that they were scared,” Polverino told the Times. “But they also got unhealthy.”

To tease out this ecology of fear — sort of an invasive fish vulnerability profile, as Polverino put it — the researchers put an updated version of their robotic predator into tanks containing both mosquitofish and other down-under denizens. Both were plucked from the wild.

Robo-bass 2.0: The new robo-predator is pretty high tech. While the previous version was already designed to look and move like the real thing, the new robot is armed with a computer vision system that helps it tell the invasive fish from the natives.

When it spied a mosquitofish attempting to attack one of the natives, the robot predator snapped into action, lunging at the mosquitofish to force it away. (The Aussie tadpoles weren’t familiar with or scared of largemouth bass, so they swam about blissfully.)

The mosquitofish were scared off, but the impact lasted long past the initial attack.

The robot bass frightened the mosquitofish, impacting their behavior, bodies, and reproduction.

“The robot simulated realistic attacks toward mosquitofish when it approached the tadpoles, which we found changed the behaviour of the entire group of mosquitofish, in that they were less active and more anxious, and therefore less of a threat for the tadpoles,” Polverino said.

Now facing what they believe to be a threat, the invasive fish shifted into survival mode. The fish stayed in schools in the middle of the tank, even when they changed tanks, Ars Technica reported.

Even weeks after their brush with the robot — which, Ars pointed out, is a pretty long time for a fish that lives roughly a year — the mosquitofish were more worried about their new threat than reproducing, and their sperm and egg numbers dropped. The invasive fish also got smaller, as their bodies changed to make them more ready for escape.

“Brief exposures to the robotic predator have long-term consequences on mosquitofish behavior—altering their routine activity and feeding rate weeks after exposure,” the researchers wrote in their study.

“We use the fear, the innate fear that they have for this native predator,” Polverino told Ars.

The researchers harnessed the innate fear the fish have for their natural predator — the “ecology of fear.”

Future fish: The research suggests that robotic guardians may be able to fight invasive fish (and perhaps other animals too) not only by direct action but by cultivating the ecology of fear.

Their previously friendly environment now suddenly threatening, mosquitofish and their ilk may not be able to dominate the locals as easily.

If the idea works, scientists may be able to combat invasive species with robots, helping to avoid inadvertent ecological disasters, like when the sugar industry introduced mongooses to Hawaii — mongooses that started eating the eggs of endangered sea turtles instead of rats.

It’s important to note that this study is still proof of concept, however, with actual use likely years away; more testing needs to be done, especially in the field. Ars reported that the small ponds of the Edgbaston Conservation Area, home of the endangered goby, could be just such a proving ground.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.