Pennsylvania researchers have identified a particle that could explain how young blood transfusions combat signs of aging in older mice — but can the discovery help humans live longer, healthier lives, too?

The challenge: Over the past 15 years, researchers have discovered that blood from younger mice appears to reverse signs of aging in older ones — after receiving transfusions, senior rodents are quicker, heal faster, perform better on cognitive tasks, and more.

No one has managed to recreate the success of these studies in humans, though, and even if young blood transfusions could turn back the hands of time in people, it doesn’t seem like a viable anti-aging treatment — whole blood can transmit infections, cause allergic and immune reactions, and lead to other health problems.

“Like a message in a bottle, EVs deliver information to target cells.”

Why it matters: If scientists can figure out exactly what it is in the blood of young mice that combats aging in older ones, we might have a better shot of replicating the success of these mouse studies in humans.

We could then use that knowledge to create a pill or other treatment to deliver the benefits of young blood transfusions without the need for actual blood — ideally, synthesizing the fountain of youth in a pharmaceutical lab.

The idea: Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) have now identified a kind of particle in the blood of young mice that appears to play a role in rejuvenating the cells and muscles of old mice.

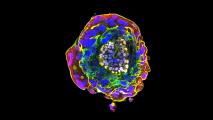

These particles are called “extracellular vesicles” (EVs), and they serve as shuttles between cells, delivering proteins, lipids, and genetic instructions between them.

“We wondered if extracellular vesicles might contribute to muscle regeneration because these couriers travel between cells via the blood and other bodily fluids,” lead author Amrita Sahu said. “Like a message in a bottle, EVs deliver information to target cells.”

If the researchers removed EVs from the young serum, the mice recovered at the same speed.

The study: For their study, the researchers injected blood serum from younger mice into mice with injured muscles. As expected, the mice who received the young blood transfusions recovered more quickly than those that received a placebo.

If the researchers removed EVs from the serum, though, the mice recovered at the same speed as those in the control group.

The team then took a closer look at the particles that had been filtered out. It appears that the EVs deliver instructions on how to create a specific protein linked to longevity (Klotho) to a type of stem cell that helps with muscle regeneration.

The EVs of older mice contained far fewer copies of these instructions than the EVs of younger mice, which resulted in their cells producing less of the helpful protein.

Looking ahead: We still don’t know if this discovery about EVs, Klotho, and stem cells in mice will translate to humans — nor does it explain all of the benefits of young blood transfusions in rodents, just their impact on muscle regeneration.

“EVs may be beneficial for boosting regenerative capacity of muscle in older individuals.”

Fabrisia Ambrosio

But it gives longevity researchers a new thread to pull, and the Pitt team is already looking ahead to how it might be applied to people.

“EVs may be beneficial for boosting regenerative capacity of muscle in older individuals and improving functional recovery after an injury,” senior author Fabrisia Ambrosio said. “One of the ideas we’re really excited about is engineering EVs with specific cargoes, so that we can dictate the responses of target cells.”

The big picture: Young blood transfusions aren’t the only interesting thread in longevity research. The DNA of people who live extremely long lives is also a promising research target, and there’s plausible evidence that we might find an anti-aging treatment hidden within fruit, feces, and castrated sheep.

Of course, it’s also possible that we won’t be able to create some pill that helps us live longer, healthier lives, in which case we’ll have to fall back on the approach doctors have been pushing for decades: exercising and eating right.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.