Instead of using land for either energy or agriculture, a new field called “agrivoltaics” does both — using the shade of solar panels to reduce farms’ water consumption and help plants thrive in a changing climate.

The challenge: Farmers in many parts of the world are dealing with water shortages, and experts predict many crops will require more water in the future in response to climate change — a situation that will make it harder for us to feed the growing population.

To deal with that, we need to combat climate change. That means trading carbon-emitting energy sources for clean renewables, and solar is currently the cheapest source available.

Solar farms need land, though, and in some places, locals have fought against installations on undeveloped land and won — with arguments ranging from the solar farms having a negative impact on tourism to taking homes away from endangered species.

Some plants require 50% less water when grown in the shade of solar panels.

Two birds, one plot of land: Agrivoltaics offers a solution to both of these problems.

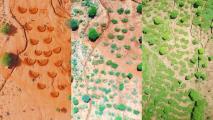

The concept, which has been around since the 1980s, centers on the use of one plot of land for farming and solar installations — placing the panels far enough apart (and high enough off the ground) that the land below can still be used for crops or grazing.

The concept doesn’t work for all types of plants — some, such as wheat, require too much sunlight — but alfalfa, sweet potatoes, lettuce, and many other crops grow well in partial sunlight.

“We’re just using these oh duh principles to try to make a more sustainable food system.”

Greg Barron-Gafford

The intermittent shade the solar panels provide over the day reduces evaporation, so farmers can decrease water consumption by growing plants under them — Greg Barron-Gafford, an agrivoltaics expert from the University of Arizona, has found that some plants require 50% less water when grown this way.

“If you spilled your water bottle in the shade versus out in the sun, where’s it going to stay wet longer? In the shade,” he told the Counter in March. “So we’re just using these oh duh principles to try to make a more sustainable food system.”

Meanwhile, the water that does evaporate helps cool the solar panels, increasing their efficiency. Developers don’t have to secure unused land for their solar installations, and farmers get an additional source of income.

Jack’s Solar Garden generates enough energy for 300 homes and produces 8,000 pounds of produce yearly.

The legal hurdle: Agrivoltaics proponents may have partly avoided push-back from NIMBYs, but they have run up against another challenge: land-use laws.

When the family that owns the largest agrivoltaics project in the U.S. — Jack’s Solar Garden in Colorado — first approached county regulators about installing solar panels on their farm, they were told they couldn’t because it was designated as historic farmland.

After some back and forth, they were eventually able to secure permission, and today, the farm generates enough energy for 300 homes, while also producing 8,000 pounds of produce per year.

Looking ahead: Such government support of agrivoltaics will be key to growing the industry, according to experts — and to Byron Kominek, owner of Jack’s Solar Garden, approving the dual use of land just makes sense.

“The question for policymakers and landowners is, are we going to be taking out a lot of arable land … and just putting in solar panels and having weeds grow underneath them?” he said in an interview with WIRED. “Or are we going to create regulations that help to keep that soil active, to help it keep doing productive things, like it has been doing over the previous decades or centuries?”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.