Magnetoreception — the ability of some animals to sense magnetic fields — is one of those remarkable abilities that is so alien to us that it’s difficult to grasp.

It’s not just stoners watching the Discovery Channel and fans of the X-Men who marvel at magnetoreception, either. Science has had a devil of a time explaining just how animals — including migratory birds, sea turtles, eels, and bats — can sense the Earth’s magnetic field.

Researchers at the University of Tokyo have taken a big step towards figuring it out: they’ve observed, for the first time, living cells reacting to magnetic fields, New Atlas reports.

Their study, published in PNAS, provides evidence supporting the “radical pair mechanism” theory of magnetoreception. (As opposed to the theory that suggests a relationship with magnetic-sensing bacteria.)

As New Atlas explains, when certain molecules are excited by light, their electrons can jump to neighboring molecules, creating a radical pair — two molecules with a single electron each.

The spin rate of those electrons changes the chemical reactions of the molecules. Because magnetic fields can alter an electron’s spin rate, the theory goes, they may be causing chemical changes in an animal’s cells that alter its behavior — magnetoreception.

Scientists believe the most likely culprits for radicalization to be a class of proteins called cryptochromes.

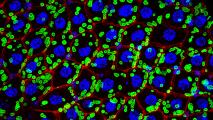

Tokyo researchers Noboru Ikeya and Jonathan R. Woodward turned their attention to the flavin molecules in HeLa cells — a human cell line commonly used for research (originating in cervical cancer cells in Henrietta Lacks). Per New Atlas, flavin molecules are a type of cryptochrome that glow when exposed to fluorescent light.

Ikeya and Woodward irradiated the HeLa cells with fluorescent light, causing the flavin molecules to glow, then swept a magnetic field over the cells at four second intervals. When exposed to the field, the cell’s fluorescence dropped 3.5%; evidence, the researchers propose, of the kind of chemical reaction you’d see in a radical pair.

“We’ve not modified or added anything to these cells,” Woodward told New Atlas. “We think we have extremely strong evidence that we’ve observed a purely quantum mechanical process affecting chemical activity at the cellular level.”

It’s important to note the researchers used magnets roughly equivalent in strength to the kind holding wedding invitations on your fridge — much stronger than the Earth’s background magnetic field. But weaker fields actually affect electron spin rate more — more support for the theory that magnetoreception stems from the radical pair mechanism.

This is a first-of-its-kind observation; it’s exciting, but it’s still too soon to say we’re … positive these chemical changes are the cause of magnetoreception.