When a woman is between the ages of 15 and 49, she’s in her reproductive years. She’s also more likely to die from an AIDS-related illness than anything else.

Now, an in-development vaginal ring shows promise at both protecting a woman from the AIDS-causing virus HIV and giving her control over her fertility.

What Is a Vaginal Ring?

In Ancient Egypt, women used to insert a mix of crocodile dung and sour milk into their vaginas to prevent pregnancy — thank goodness birth control development didn’t stop there.

Today, women have a slew of much safer, much more effective options for contraception, from pills and patches to implants and shots.

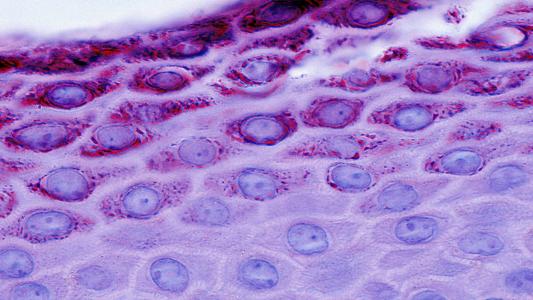

Many of these devices work by delivering hormones that stop the ovaries from releasing an egg each month. Without an egg in the uterus, there’s nothing for sperm to fertilize, meaning a woman can’t get pregnant.

A vaginal ring falls into this category of hormonal birth control. A woman inserts it into her vagina, and it releases hormones that prevent ovulation for three weeks. She removes it, has her period, and then inserts a new hormone-laden ring.

This method is ideal for some women. It’s more convenient than a daily pill, but it’s also very easy to stop using if they decide they want to get pregnant — other equally convenient methods, such as implants, require a trip to the doctor for removal.

HIV Prevention

Women may have many options for birth control today, but their options for HIV prevention are far more limited.

Women are most likely to contract HIV from sex with an HIV-positive partner. Condoms can decrease the risk of transmission, but a partner’s condom-usage isn’t entirely within a woman’s control.

She can take an oral medication called PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) to decrease her risk of contracting HIV, but, like the birth control pill, those meds usually have to be taken daily, which can be inconvenient and easy to miss.

A once-per-month PrEP injection has been approved for use in the U.S., Canada, and the European Union, but that must be administered by a healthcare professional.

Women want and need new multipurpose prevention choices they can use on their terms.

Bríd Devlin

The WHO recently recommended a new option for HIV prevention: a vaginal ring that releases the HIV-targeting drug dapivirine.

The ring is designed to be replaced every 28 days, and while it doesn’t provide the same level of protection as condoms, studies show it can decrease a woman’s risk of contracting HIV by up to 35%.

Now, researchers at the Microbicide Trials Network and the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM) have announced the promising results of a small study testing a vaginal ring that releases both dapivirine and the ovulation-preventing hormone levonorgestrel — and this ring works for 90 days.

Two-in-One Protection

During the study, 25 women used the new vaginal ring for 90 days while having the levels of dapivirine and levonorgestrel in their blood plasma and vaginal fluid measured periodically.

Some of the women were instructed to keep the vaginal ring in for all 90 days, while others were told to remove it for two days every month.

(This was to study whether periodic removal would affect the ring’s ability to protect against HIV and pregnancy, as well as what effect it might have on irregular bleeding, which is a common side effect of levonorgestrel.)

“(A)s a user-controlled product, periodic removal of the ring can be expected,” researcher Sharon L. Achilles said in a press release.

The bleeding patterns were almost identical between the two groups, and no serious safety concerns emerged during the study. The levels of levonorgestrel remained high enough to protect against pregnancy throughout the study for women in both groups.

While participants had the new vaginal ring in place, they had higher levels of dapivirine (the HIV preventative) in their blood plasma than users of the 28-day ring did during a previous study. When the ring was removed, the levels decreased, but were still in the same range as the 28-day study.

The levels of dapivirine in vaginal fluid, however, dropped quickly and dramatically after removal of the vaginal ring, which could affect its ability to protect against HIV.

“(I)t remains to be seen whether or not periodic removals will allow for sustained protection against HIV infection,” Achilles said. “This is something that we will need to study further.”

We are optimistic that the vaginal ring will further expand women’s health choices.

Bríd Devlin

The researchers also plan to test a new design they think will help the vaginal ring stay in place — 19 of the 25 participants said it partially fell out on its own during the study, and for 10 women, it completely fell out at least once.

The design might still need some work, but the researchers are encouraged by the results of their study.

“We have heard from women around the world that they want and need new multipurpose prevention choices they can use on their own terms,” Bríd Devlin, IPM’s executive vice president for product development, said in the press release.

“We are optimistic that the dapivirine-contraceptive ring will further expand women’s sexual and reproductive health choices,” she added.

Editor’s Note, 5/17/21, 3:40 ET: The title and subtitle of this article were updated to clarify that the ring has not yet undergone efficacy testing.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.