Scientists have sequenced the DNA from the ear bone of an ancient cave bear — an extinct relative of the polar and brown bears.

It may come as a surprise that the 360,000-year-old genetic material even survived the test of time. Until now, any preserved DNA that old had been frozen in permafrost, like the million-year-old mammal teeth that recently made headlines. Because DNA decays over time, the really old stuff needed to be kept on ice. This also limited genetic studies of extinct animals to those that roamed the polar regions.

But this cave bear’s bone was found in a temperate climate (in what is now the country of Georgia), where DNA degrades more quickly. This new research shows that the opportunity for genetic analysis could be much greater, both in space and time, than we realized.

“With DNA, we can decipher the genetic code of extinct animals long after they’ve gone, but over thousands of years, the DNA present in ancient samples slowly disappears, creating a time limit of how far back in time you can normally go,” Axel Barlow, a paleogeneticist from Nottingham Trent University, said in a statement.

“Our study shows that this amazing molecule can survive even longer than previously thought, opening up new opportunities for genetic investigation over previously unimaginable timescales.”

Cave bears once roamed the Eurasian continent until they went extinct about 24,000 years ago, during the peak of the last Ice Age. They coexisted and interbred with the brown bear, and the modern brown bear still has traces of the cave bear genome.

Larger than brown bears, the huge vegetarians got their name from hibernating in caves during the winter, where many died because they hadn’t fattened up enough. The researchers from Nottingham Trent University and the University of Potsdam in Germany used an ear bone found in the Kudaro Caves, in the Southern Caucasus Mountains, for their genetic research.

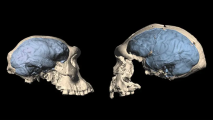

The team extracted DNA from the bone, and then they used a computer to sort through the billions of short DNA fragments. By comparing it to a reference genome from the modern brown bear, they were able to weed out contaminating DNA — likely from bacteria and fungus that had been picked up over the years — and reassemble the ancient genome.

Their results, published in Current Biology, confirm that the polar bear and brown bear, the cave bear’s living relatives, all had a common ancestor. Their evolutionary lineages split about 1.5 million years ago.

“Interestingly, these separations happen pretty much around the time when the ice age cycles became more extreme, so it looks like climate has influenced the evolution of these bear species quite a bit,” Michael Hofreiter, the senior author of the study and a researcher at the University of Potsdam told Gizmodo.

In terms of evolutionary lineage, the separation of brown, polar, and cave bears, and the end of interbreeding between the cave and brown bears, all happened about one million years ago, when the planet became colder, and ice ages were long and intense.

The cave bear started to disappear near the first signs of early humans, who painted images of cave bears, and their spear points have been found in some cave bear bones. But the bear that this ear bone belonged to could have lived before our species, Homo sapiens, even existed.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.